Gargzdai and the Holocaust

by

John S. Jaffer

Table of Contents

I. Jewish Residents of Gargzdai killed in the Holocaust

II. Einsatzgruppe A

IV. Killing of the Jewish Men of Gargzdai

V. Killing of the Jewish Women and Children

VI. Orders to Einsatzkommando Tilsit

VIII. Discrepancy between German and Soviet Records as to Number of Victims at Men's Killing Site

IX. Did Jewish civilians take up arms against the invasion?

I. Jewish Residents of Gargzdai killed in the Holocaust

The total number of Jewish residents

killed in or near Gargzdai is at least 500: 200 men (and one woman)

killed on June 24, 1941, and 300 women and children killed on

September 14 and 16, 1941.

Yad

Vashem has posted online its Central

Database of Shoah Victims' Names. A search for the location Gargzdai

or Gorzd yields a list of 714 names as of April, 2017, but this

total includes instances of multiple entries for single individuals. A

search for the town name yields persons killed in Gorzd, and those born

in Gorzd who perished elsewhere. Each name is linked to further

information from the report in the Yad Vashem archives, as well as a

copy of the report. This site is an invaluable resource for anyone

researching Gorzd.

A list containing names of 78 victims was compiled by

the Gargzdai Town Secretary during the War: Jewish

residents of Gargzdai killed in June and September, 1941. The

original list is now kept at Gargzdai Area Museum.

The Court Judgment in Ulm (Vol XV, Case. No. 465,

summarized here),

1958, lists twelve Jews from

Memel killed in Gargzdai.

The figure of 200 men and one woman is set forth in

the German trial records, and is supported by written reports by the

perpetrators nearly contemporaneous with the killings. The figure

of 300 women and children is set forth in Pinkas

Hakehillot

Lita and on

the

monument at one of the two women's sites.

Soviet investigations before the end of the war

included exhumation of the killing sites: "Act about Slaughter of Civil

Soviet People by Fascist Aggressors on the Temporary Occupied Territory

of the Gargzedai [sic] Volost, the Kretinga Uyezd, the Lithuanian

SSR," The Tragedy of Lithuania: New Documents on Crimes of

Lithuanian Collaborators during the Second World War, ISBN

978-5-903588-01-5, pp. 205, 219, formerly online at

http://common.regnum.ru/documents/the-tragedy-of-lithuania.pdf. (cited

below as Tragedy).

According to the report dated February 11, 1945 the killing site within

the town of Gargzdai contained bodies of 396 men shot by firearms. At

the women's sites in the forest, the Soviet report states that one of

the mass graves contained 107 "girls," while the other contained 347

women and children. The report dated April 11, 1945 gives a total of 850

"innocent Soviet citizens - men, women and children" killed in Gargzdai,

a figure which the report says was confirmed by opening the graves and

through the testimony of three witnesses.

The events surrounding these killings are set

forth below.

translation of the inscription of the women's monument, referring to 300 victims, is found at the Holocaust Atlas of Lithuania.

There is an apparent discrepancy between the German records and the Soviet report as to the number of victims at the men's site. This discrepancy is discussed in Section VIII below.

The Tragedy of Lithuania: New Documents on Crimes of Lithuanian Collaborators during the Second World War was first noted at the Resources page of the KehilaLinks site for Trashkun (Troskunai), Lithuania.

Aus den Häusern von Garsden wurden

dann noch weitere männliche Juden sowie einige

kommunistenverdächtige Personen herausgeholt und ebenfalls

in Richtung Reichsgrenze abgeführt. (p. 95).

(Out of the Garsden houses

further male Jews as well as some suspected Communists

were taken and led in the direction of the border.)

Unter

den Gefangenen befand sich auch eine Frau, die

Ehefrau eines russischen Kommissars. Ob sie von

Anfang an unter den Gefangenen war oder ob sie erst

später zugeführt wurde, konnte nicht geklärt werden.

(p. 103).

(The

prisoners also included a woman, the wife of a

Russian commisar. Whether she was part of the

original prisioners, or was brought there later,

could not be clarified.)

.....

Bei

den Gefangenen handelte es sich mit Ausnahme

von wenigen litauischen Kommunisten nur um

Juden, vom Jugendlichen bis zum Greis. (p.

102).

(Among the

prisoners, with the exception of a few

Lithuanian Communists, were only Jews, from

youths to elderly.)

The Stahlecker Report contains separate subtotals for Jews and Communists killed in the Kovno district: " Jews 31,914 Communists 80 Total 31,994" (Enclosure 8).

Thus within the Kovno district, the reported victims separately categorized as Communists rather than Jews represented less than three tenths of a percent. Overall within the three Lithuanian districts, the reported Communist victims represented approximately one percent of the total.

II. Einsatzgruppe A

Germany invaded the

Soviet Union beginning

on June 22, 1941.

Mobile killing squads

known as

Einsatzgruppen

followed the German

Army into the occupied

areas. There were four

Einsatzgruppen (A, B,

C and D), which were

in turn divided into

smaller units called

Einsatzkommandos and

Sonderkommandos.

Einsatzgruppe A,

commanded by SS -

Brigadeführer Walter

Stahlecker, carried on

mass executions of the

Jewish population in

Lithuania and other

Baltic areas.

Einsatzkommando 3 (a

subunit of

Einsatzgruppe A)

operated in Lithuania.

The deeds of

Einsatzkommando 3 were

set forth in an

infamous document

known as the Jäger

report, which was

dated December 1,

1941. In

that document Karl

Jäger, commander of

Einsatzkommando 3, set

forth totals of

executions by location

in Lithuania. The

executions outlined in

the report began on

July 4, 1941, and

totaled over 137,000.

The Gargzdai killings

are not included in

the Jäger

report.

The execution of the

Jewish men in Gargzdai

took place on June 24,

1941, prior to the

first execution listed

in the Jäger report.

These killings in

Gargzdai were the

first mass execution

following Germany's

invasion of the Soviet

Union on June 22,

1941, and may be

regarded as the start

of the Holocaust.

The group which

perpetrated the

killings is sometimes

called Einsatzkommando

Tilsit. Tilsit

was in East Prussia,

close to the border

with the Soviet Union.

Einsatzkommando Tilsit

was not formally part

of Einsatzgruppe A,

but acted as an

adjunct to it.

The Tilsit unit was

commanded by SS-Major

Hans - Joachim Böhme,

and composed of

personnel from the

Gestapo and Security

Service in Tilsit, as

well as police from

Memel (led by

Oberführer Bernhard

Fischer-Schweder) and

Memel Border

Police. It

committed mass

executions in the area

of the Soviet Union

close to the border

with Germany.

The

killings by the Tilsit

unit were reported to

Berlin in the same

"Operational Situation

Reports" which

reported the killings

by Einsatzgruppe

A. Report No.

12, dated July 4,

1941, states that

Stapo Tilsit

had

so far carried out 200

shootings. These

are evidently the

shootings in

Gargzdai. Report

No. 14, dated July 6,

1941, lists the

killings in Garsden

(the German name for

Gargzdai), as well as

in Krottingen

(Kretinga) and

Polangen (Palanga).

The Report lists these

killings under the

heading of

Einsatzgruppe A, but

states that "Tilsit

was used as a base"

for these "major

cleansing operations."

The Report sets forth

that 201 persons were

executed in Garsden,

and gives a cover

story to explain the

Garsden shootings -

that the "Jewish

population had

supported the Russian

border guards."

Similar cover stories

were given with regard

to the other two

towns.

In

Report No. 19, dated

July 11, executions in

additional towns are

attributed to "Stapo

Tilsit," including

Tauroggen (Taurage),

Georgenburg

(Jurbarkas), and

Mariampol

(Marijampole). The

author no longer found

it necessary to give

any supposed excuse

for the executions.

In

Report 26, dated July

18, a total of 3302

executions are

attributed to "Police

Unit - Tilsit," and

these are set forth

separately from

Einsatzgruppe A.

Stahlecker later wrote

a document dated

October 15, 1941,

known as the

Stahlecker Report,

which referred to a

total of 5502 killed

by State Police

Security Service

Tilsit.

The

summary figures in

Report 26 and the

Stahlecker Report

presumably include the

201 persons previously

reported as killed in

Garsden.

Scholars have more

recently discovered in

the archives of the

former Soviet Union Report

from

Staatspolizei Tilsit to RSHA, July 1, 1941.

This document was evidently used as a source for

Operational Situation Report No. 14 (which was dated

five days later), and also contains additional

information.

Several members of Einsatzkommando Tilsit were prosecuted by the West German Government for War Crimes. These trials took place in Ulm and Dortmund, West Germany, for crimes including the killings at Gargzdai/Garsden. Summaries of War Crimes prosecutions related to Gargzdai (including the sentences) are located at the site for the University of Amsterdam.

IV. Killing of the Jewish Men of Gargzdai

The Court in Ulm

entered a lengthy

Judgment which is

a major source of

information about

the Gargzdai

killings.

This Judgment is

now available

online (Vol

XV, No. 465).

It was published

in Justiz und

NS-Verbrechen,

Vol. XV,

University Press

Amsterdam (1976),

and in KZ-Verbrechen

vor deutschen

Gerichten, Band

II:

Einsatzkommando

Tilsit - Der

Prozess zu Ulm,

(Frankfurt am

Mein: Europaïsche

Verlagsanstalt,

1966). The

judgment is

summarized in the

Gorzd

Yizkor

Book, pages 75-79 [Image 426]. Further

information about the killings is contained on

page 38 of the Gorzd

Yizkor Book [Image 463].

Two letters about the killings

are posted at the JewishGen Yizkor Book Project.

One is a letter in the Gorzd Yizkor Book from

Leyb Shoys (or Leibke

Shauss), dated February 5, 1945, page 342-344

[Yiddish section]. Shoys had returned to Gargzdai,

collected information from town residents, and

wrote this report to his brother in South Africa

about the killings. A similar letter from Shoys to

his uncle Khaim Shoys in America is set forth in

the book Lite, as the Chapter titled "The

Destruction

of Gorzd". Lite gives the name only

of the uncle who received the letter and not the

nephew who wrote it, but the Gorzd Yizkor Book,

page 38, identifies the author as Liebke Shauss.

Further details are contained

in the Gorzd Chapter in Pinkas Hakehillot Lita, also posted at the JewishGen Yizkor

Book Project.

In the Court Judgment, the

following facts are reported:

At the time of the attack,

Gargzdai had a population of around 3000, of which

600-700 were Jews. This included Jewish

refugees who had come from Klaipeda/Memel after

Germany annexed the Memel Territory in 1939.

Germany attacked at 3:05 AM on

June 22, 1941. There was heavy resistance by

the Soviet army, and the town was not secured

until the afternoon of June 22. During the

fighting, most of the civilians hid in a cellar,

and much of the town was burned.

The Gestapo and SD (Security

Service) from Tilsit began to round up the Jewish

men, as well as suspected Communists, for

execution. They were held overnight in the

park. The males were forced to work on

defense trenches, an old rabbi was abused, and a

Jewish boy was shot for allegedly not working hard

enough.

On June 24, the men were led to

a trench. They were shot by a firing squad

consisting of 20 persons, including the Tilsit

personnel as well as police from Memel. Some

of the victims who were refugees from Memel knew

their executioners among the Memel police. The

total number executed on that day was 201 persons.

The Shoys letters add some

additional details. The men were kept without food

or water until the 24th. The shootings took place

near a house belonging to David Wolfowitz, at

around 1:00 PM.

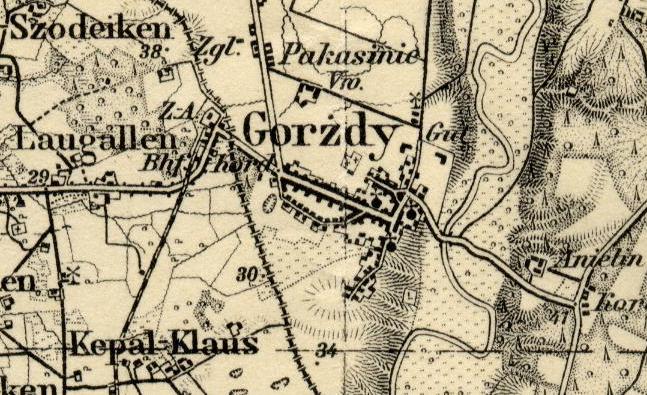

The Gorzd

Yizkor Book [Image 463] states that the

killings took place in a field at the end of

Tamozhne St. A town diagram in the book

[Image 13] shows this name for the main street

leading west to the old border and Laugallen.

("Tamozhnya" is the Russian word for "Customs.")

The Report of Staatspolizei Tilsit states that the

201 persons killed on June 24, 1941 included one

woman. The persons committing the shooting were

selected by the police director in Memel, and

consisted of 30 men with one police officer.

According to a Soviet report

dated February 11, 1945, exhumation of this site

revealed a total of 396 men, killed by firearms. "Act about Slaughter of Civil Soviet

People by Fascist Aggressors on the Temporary

Occupied Territory of the Gargzedai [sic]

Volost, the Kretinga Uyezd, the Lithuanian SSR," The

Tragedy of Lithuania: New Documents on Crimes of

Lithuanian Collaborators during the Second World

War, ISBN 978-5-903588-01-5, p. 219.

The oldest known photograph of

the men's killing site from ground level was taken

by George Birman when he visited Gargzdai in

April, 1945. This photo is posted online at the

collection of George

Birman papers at the United States Holocaust

Memorial Museum, Album 2, 1944-1946, Item

9, top row, second photo from left.

V. Killing of the Jewish Women and Children

The

women and

children of

Gargzdai were

initially

rounded up at

the same time

as the men.

After the men

were killed,

the women and

children were

kept prisoner

for several

months.

The Gorzd

Memorial book

and the Shoys

letters say

they were kept

in the village

of Anelishke

and forced to

perform hard

labor.

Then, during

September of

1941, they

were taken to

the woods

northeast of

Vezaiciai, on

the road to

Kule (Kuliai).

The Gorzd Book

says the

children were

killed by the

Germans with

bayonets, and

their mothers

and

grandmothers

killed two

days later.

(Memorial

Book, p. 38).

The Court

Judgment

points to

statements

that women and

children from

Garsden were

killed by

"betrunkene

litauische

Hilfspolizisten"

(drunken

Lithuanian

auxiliary

police) in

August/September

1941, but

further states

the Court

could not

determine if

Gestapo

personnel were

involved.

The Court

concluded that

a minimum of

100 were

killed.

The monument

at one of the

women's

killing sites

states that

the killing

occurred in

October, 1941,

and 300 were

killed. Yosif

Levinson, Skausmo

Knyga - The

Book of Sorrow

(Vilnius: Vaga

Publishers,

1997), page

110. However,

the monuments

are not

necessarily

accurate

sources of

information as

to dates. The

monument at

the men's site

in Gargzdai

has a clearly

erroneous date

of July, 1941

despite the

known date of

June 24. Pinkas

Hakehillot

Lita

gives the

dates of the

women's

killings as

September 14

and 16, and

states that

about 300 were

killed. The

same dates of

September 14

and 16 are

given by Dr.

Hershl

Meyer in the

Gorzd Memorial

Book, p. 38.

There was one

survivor of

the women's

shooting,

Rachel (or

Eyne) Yami,

who provided

chilling

detail to Leib

Shoys which is

set forth in

his

letters.

Because the

former

residents of

Gorzd would

want to know

the dates of

the killings,

it is

reasonable to

suppose that

Rachel Yami

was the source

for the dates

of September

14 and 16 set

forth in

Pinkas

Hakehillot

Lita and by

Dr. Meyer.

A Soviet

investigation

included an

exhumation of

the sites, "Act

about

Slaughter of

Civil Soviet

People by

Fascist

Aggressors on

the Temporary

Occupied

Territory of

the Gargzedai

[sic]

Volost, the

Kretinga

Uyezd, the

Lithuanian

SSR," The

Tragedy of

Lithuania: New

Documents on

Crimes of

Lithuanian

Collaborators

during the

Second World

War, ISBN

978-5-903588-01-5,

p. 219, and

also the

eyewitness

testimony of a

priest, Ionas

Aleksens,

identified in

Lithuanian

sources as

Jonas

Aleksiejus. He

was riding a

bicycle from

Gargzdai to

Vezaiciai when

he encountered

the women and

children being

conveyed to

the killing

place in the

forest. He

unsuccessfully

attempted to

dissuade the

perpetrators

from

committing the

killings.

"Transcript of

Interrogation

of Witness

Aleksens

I.A.," id.

at p.

221; Dr.

Arunas Bubnys,

Holocaust in

Lithuanian

Province in

1941 at

40-43.

According to

the

exhumation,

one of the

graves

contained 107

"girls" killed

by firearms

and blunt

objects.

The other

contained 347

women and

children, with

the women

having been

killed by

firearms and

the children

by blunt

objects.

Some of the

children had

no visible

injury,

indicating to

the

investigators

that they had

been buried

alive.

The Lithuanian

Special

Archives

contain

interrogation

records of

three

participants

in these

killings.

Interrogations

are translated

here.

The questions

do not deal

with motive or

mental state

of the

perpetrators,

but merely

attempt to

establish a

sequence of

events.

In

attempting to

reconcile the

bare outline

of facts from

various

sources, two

questions

arise: 1) what

age victims

were killed on

each of the

two days, and

2) which site

in the forest

contains the

victims killed

on the first

day, and which

contains the

victims killed

on the second

day. The

information is

not entirely

consistent.

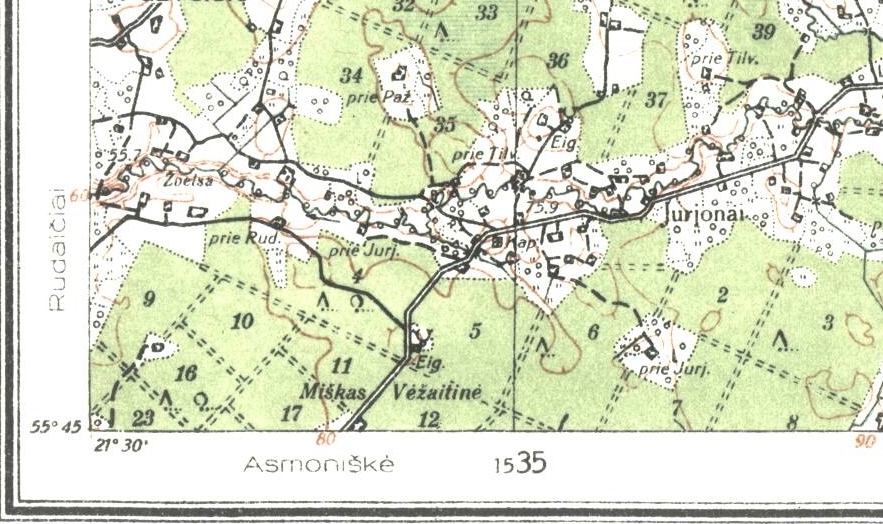

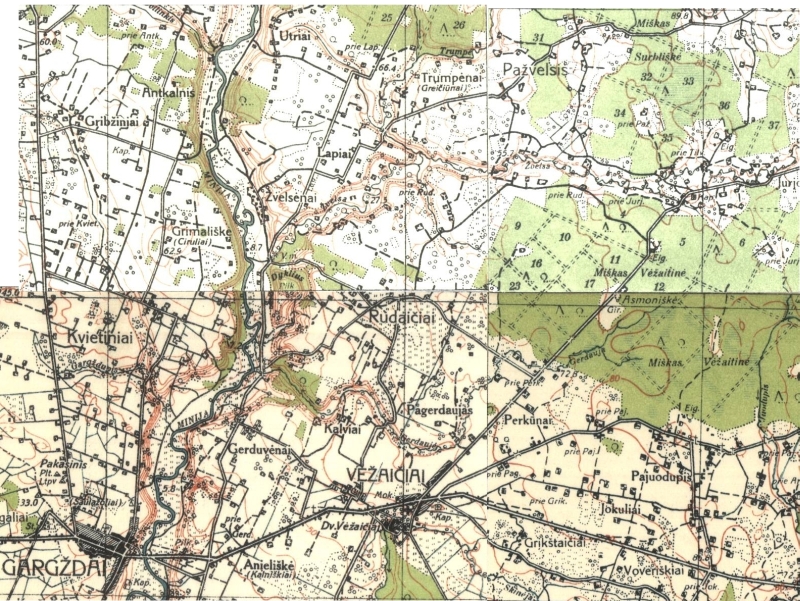

Note: Anieliske, Ashmoniske and Perkunai

Anieliske

Anieliske was the location where the women and children were held captive between shortly after the invasion on June 22, 1941, and their killing in September, 1941. It was probably the area shown on older maps as Anielin.

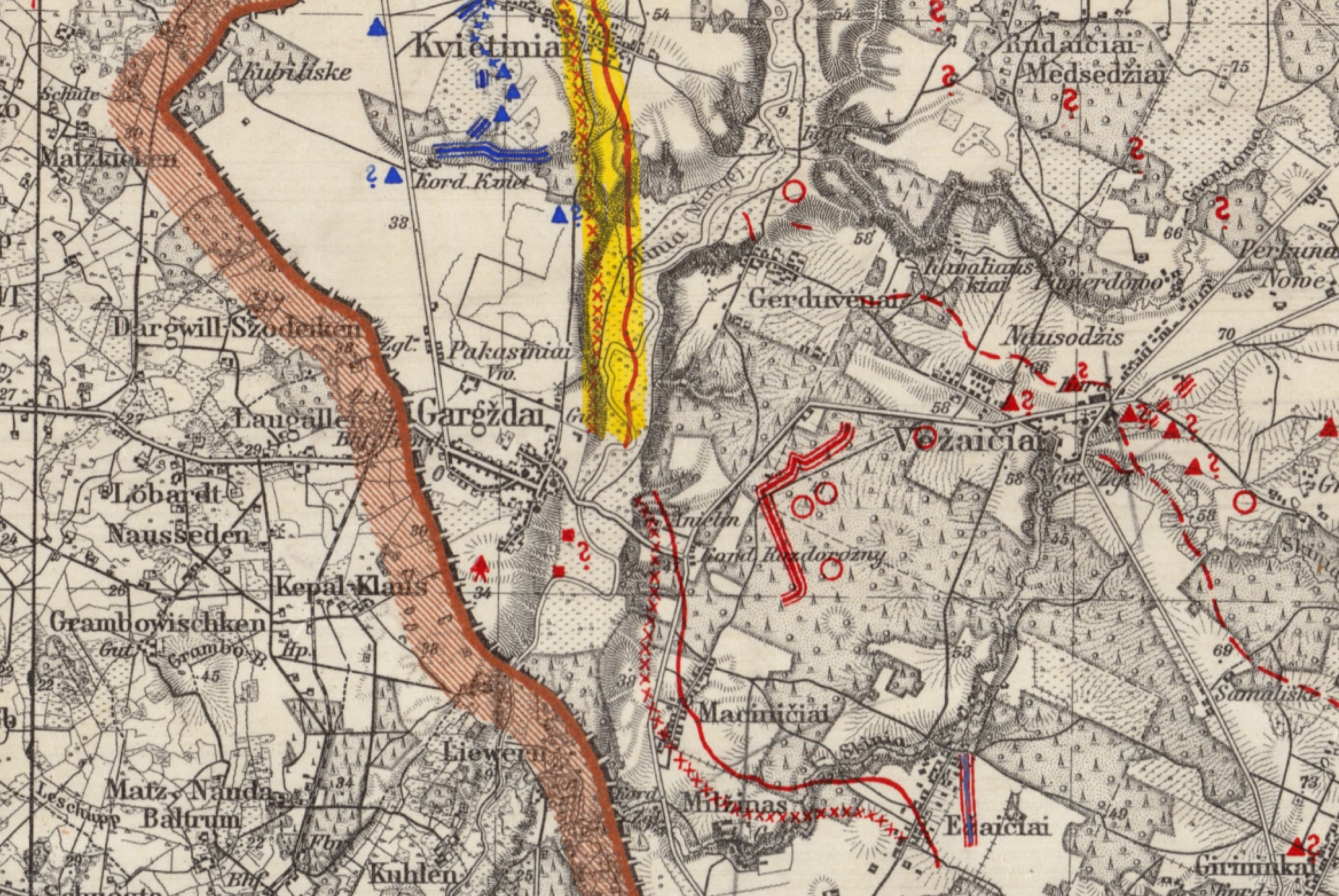

The map is ambiguous as to whether the name "Asmoniske" applies to the forest ranger station, or instead a cluster of buildings above the capital A in Asmoniske, or both. It would seem more logical that references to the village of Asmoniske would apply to the cluster of buildings on the road, rather than a forest ranger station located away from the road.

The name Oszmianiszki is shown on the 1:300,000 Übersichtkarte map of Tilsit (1939) at www.mapywig.org.

An

earlier

depiction is

on a Russian

map, 1866 -

1872:

1:126,000

Russian Map X-1

(1866-1872) at maps4u.lt

Information

about the

1:126,000

(3-verst) map

series

For

animations

comparing maps of

the Vezaitine

Forest, see here.

Perkunai

The

Lithuanian Army

map shows the

village of

Perkunai,

northeast of

Vezaiciai and

just southwest

of the

forest.

The killing of

the women and

children is

stated to be

close to this

village in The

Tragedy of

Lithuania: New

Documents on

Crimes of

Lithuanian

Collaborators

during the

Second World War,

ISBN

978-5-903588-01-5,

p. 219, 221. The

latter reference

says the killing

site is 5 km from

Vezaiciai and 27

km from Perkunai,

but evidently "27

km" is a misprint

for 2.7 km.

Measuring

from Perkunai is

ambiguous. Even

today, maps differ

as to the exact

location of this

village, which

evidently has

changed over the

years. Also it is

unclear whether

the given

measurement from

Perkunai to the

killing site is

the straight line

aerial distance,

or instead follows

the angles of the

roads.

Identification of the Two Killing Sites

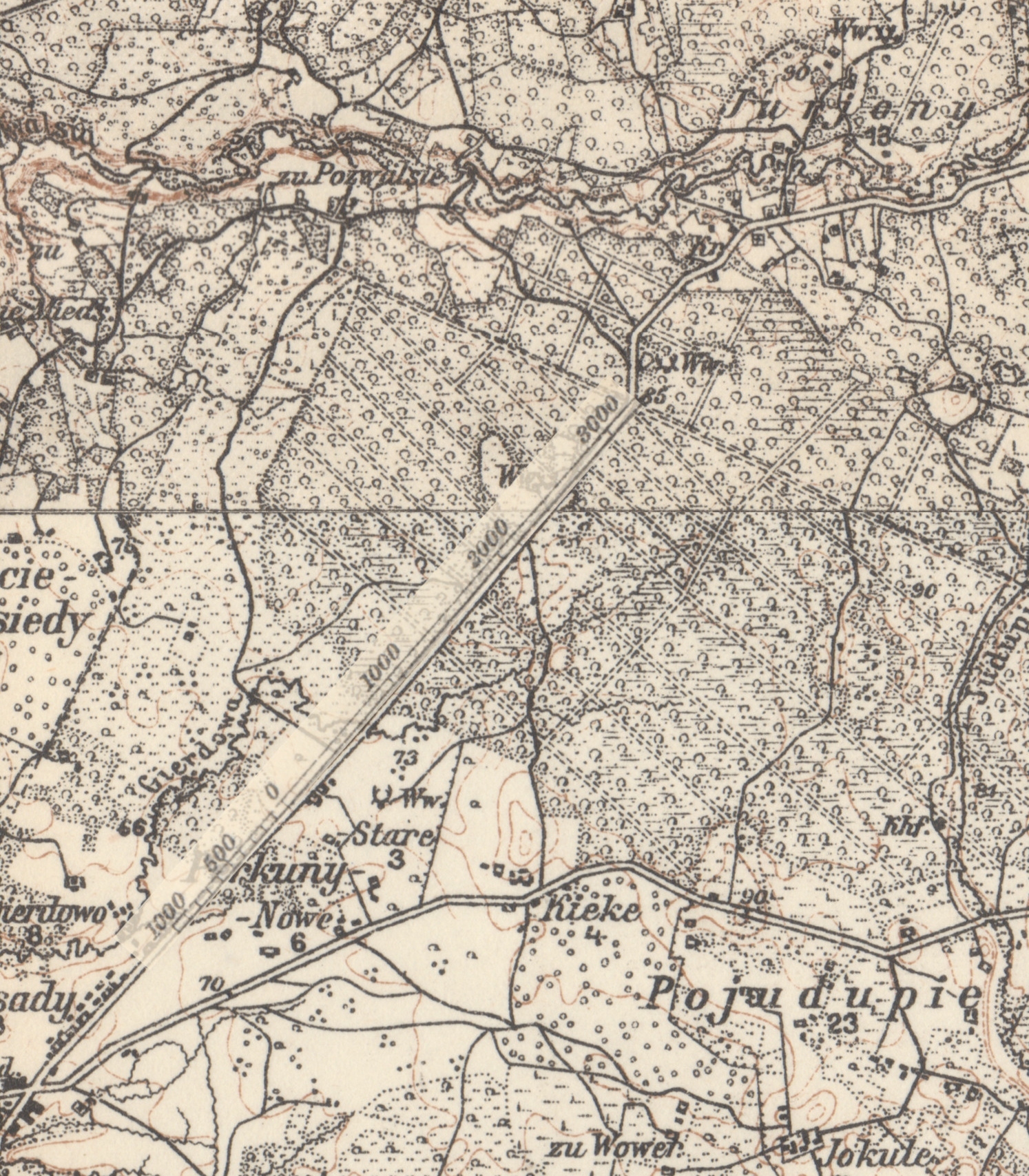

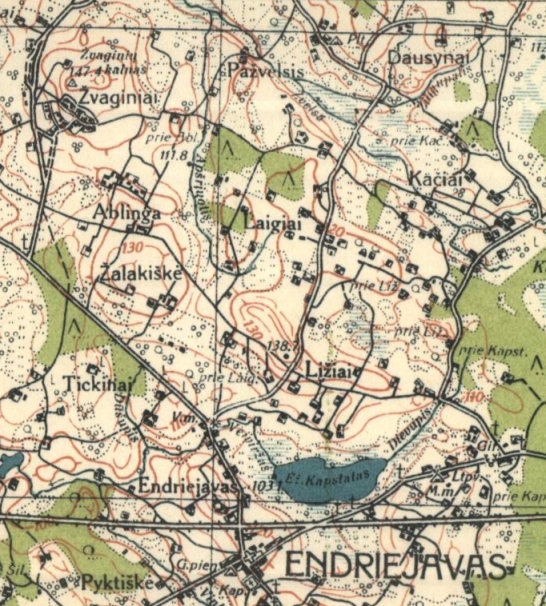

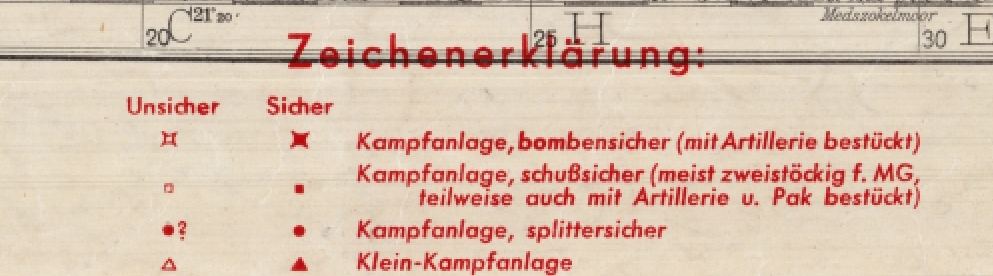

Kreiskarte (1941, but based on earlier maps) - added black dots show approximate location of killing sites

(See

Photo/Map

Comparisons of

Vezaitine

Forest)

Lithuanian

Army Topo

(1938) - added

black dots

show

approximate

location of

killing sites

On September 14, 1941 the "young women" from Gorzd were taken to the forest of Vezaiciai and killed. (Pinkas Hakehillot Lita). (Yahadut Lita).

About 100 young able

bodied women taken,

purportedly for

labor (Bubnys,

p. 42) (Gubistas

interrogation)

Exhumation of

site revealed

"107 corpses

of killed and

shot girls."

Site is 450 m.

from road. (Tragedy

p. 219).

The Second Killing

Interrogation of witness, Ionas Aleksens [sic], describes shooting of 300 women and children. (Tragedy p. 221-222).

Site is "about 27 km [sic]" from Perkunai. (Tragedy p. 221-222) (evidently a misprint for 2.7 km).

Killings were witnessed by Vezaiciai dean Jonas Aleksiejus. Bubnys, p.42.

Two

days after the

killing of the

young women,

"the rest of

the women and

children were

brought to the

same place,

and their fate

was similar."

(Pinkas

Hakehillot

Lita).

Exhumation of

site found 347

corpses of

women and

children (Tragedy

p. 219).

Identification

of the two

sites:

Co-ordinates

of SW site are

shown at Holocaust

Atlas of

Lithuania.

Google Earth

measurement

tool shows

that this site

is

approximately

440 m. from

the near edge

of Road 166,

when measured

by shortest

distance to

roadway, and

about 525 m

from road

along

north-south

direction.

Co-ordinates

of NE site are

shown at Holocaust

Atlas of

Lithuania.

Google Earth

shows that

this site is

about 2.5 km

from Perkunai

by air (i.e.

2.5 km from

wheres Google

Earth locates

Perkunai), and

about 350 m

from Road 166.

Memorial sign

at NE site

refers to the

killing of "about

300 Jewish

people of

Gargzdai."

Interrogation

of Defendant

Puzneckis,

describing

second day's

killing, says

the carts

carrying the

victims and

guards turned

into forest

about 1km

before

reaching

Ashmonishki,

and then drove

carts in

forest for

about half a

kilometer to

reach killing

site by forest

meadow.

Theory I: NE site is second day, and SW site is first day:

This is

the theory

adopted by Gedenkorte

Europa in

its section on

Gargzdai.

This German

language

website

describes the

southwest

memorial as

"Gedenkort

[Memorial

Site] II" for

the 100

selected

women, and the

northeast

memorial as

"Gedenkort

III" with its

sign (restored

in 2016)

referring to

approximately

300 victims.

Evidence supporting Theory I

Puzneckis participated in the killings on both days, and his memory may have confused the two sites.

For further

information

regarding the

route by which

the victims

were brought

to the

southwest

site, see the

notes

regarding the

Interrogations,

and the comparison

of maps and

photos of the

Vezaitine

Forest.

Another

possible

inconsistency,

set forth in Bubnys,

p. 42, is the

name of the

chief

Lithuanian

perpetrator at

the two

respective

sites. The

name set forth

in the

Aleksiejus

statement as

primarily

responsible

for the second

killings,

Idlefonsas

Lukauskas (Tragedy,

p. 222) is

named by other

sources as in

charge of the

first killings

but not the

second.

Defendant

Puzneckis

names

Lukauskas as

participating

in the second

killings,

although he

was not in

charge,

because he was

subordinate to

Police Chief

"Manchkus."

Aleksiejus

does not name

Gargzdai

Police Chief

Mockus as

present on the

second day.

Defendant

Gubistas

stated that

both Lukauskas

and Mackus

were present

the first day.

Defendant

Saliklas said

Ildefonsas was

in charge on

both days.

The account in the Ulm trial regarding the women and children ("Garsden II") is very brief in comparison to the men, comprising only three pages. (pp. 400-402). The judgment refers to only one shooting, not two. The judgment refers to "at least 100" being killed, which might suggest the account concerns the first killing per the Soviet account. However the Ulm judgment also refers to killing "women and children" which is more consistent with the second killing, per the Soviet investigation. The Court convicted Defendants Böhme and Behrendt of ordering these killings. Böhme gave the original order, which was then relayed by Behrendt.

_____________________________________________________________________________________

The German

judgment also

reports a

secondhand

account, in

which a German

witness

testified as

to hearing a

comment from

the Mayor of

Gargzdai. The

Mayor had told

the witness (a

customs

official in

Memel) that

small children

from Gargzdai

were killed by

Lithuanians on

June 23, 1941

in a small

wooded area

close to

Gargzdai. pp.

401-402. The

source of the

Mayor's

information is

not provided

in the

judgment. The

passage starts

with "Es

sollen..."

which may be

translated as

"reportedly":

Es

sollen auch schon am 23.6.1941 jüdische

Kleinkinder von Garsden dadurch durch Litauer

getötet worden sein, dass sie mit den Köpfen

gegen Bäume geschlagen worden seien, wie der

Zeuge La., der frühere Leiter des

Zollkommissariats Memel-Ost, auf Grund einer

Mitteilung des Bürgermeisters von Garsden

ausgesagt hat....

Andererseits

ist als vermindernder Faktor berücksichtigt

worden, dass nach den obengenannten Aussagen des

Zeugen La. schon am 23.6.1941 jüdische

Kleinkinder aus diesen Familien in einem kleinen

Wäldchen bei Garsden ermordet worden sein

sollen.

In "Lithuania Crime and Punishment," # 6, Jan. 1999, Joseph A. Melamed, Ed., published under the auspices of the Association of Lithuanian Jews in Israel, there is an article by Joseph Zak (Zera Kodesh), London, entitled "Infanticide - the Cruel Murder of Jewish Enfants and Babies." The author states regarding Gargzdai, on p. 130, that after the women and children were separated from the men, they were led by Lithuanian guards beyond the river to a site west [sic] of town where they were to be imprisoned. On the way, many of the children were murdered with stones and clubs. The only source given regarding any of the towns set forth in the article, is that that all the accounts were in "volume 4 of the anthology of Lithuanian Jewry which provides details on the Holocaust." The reference is apparently to Yahadut Lita, published by the Association of The Lithuanian Jews in Israel, Tel Aviv 1967 (Vol. 3) and 1984 (Vol. 4).

Yahadut Lita states that many of the children were killed on the way to the imprisonment site beyond the Minija River, their heads being bashed into trees and rocks. At the end of the Yahadut Lita article, the sources are stated:

a) Lithuania anthology, volume A.

b) L. Shaus, letters to Y. Leshem, Yad Vashem archive.

c) Rachel Osher Testimony, Bnei-Brak (Herzog dist.).

d) Ulm Trial Report.

Inquiries are underway to

determine whether Yad Vashem has

letters from Shaus to Leshem (a

major contributor to the Gorsd

Memorial Book), aside from

letters from Shaus to other

parties (here,

here

and here)

set forth or referenced in the

Gorsd Memorial Book and in

Lite. Can any reader

clarify the reference to

"Testimony, Bnei - Brak"? Is

Bnei Brak listed merely as the

residence of Rachel Osher, or

instead as a source of written

materials in addition to those

by Osher

in the Gorsd Memorial Book?

The Museum

of the Jewish

People at Beit

Hatsufot

reports that

after the men

were killed,

and while the

women and

children were

being

transported to

their place of

imprisonment,

"Many

of the

children were

murdered on

the way."

No source is

given for this

information,

but presumably

is the article

in Lithuania

Crime and

Punishment, or

Yahadut Lita

as described

in that

article.

Although the dates and chronology differ, these reports of earlier killing of the small children are somewhat parallel to four other accounts of the first killings in September:

a) In the Gorzd

Memorial Book,

p. 38 (English

Section), Dr.

Hershel Meyer

states that in

September, all

the women and

children were

taken to the

woods, the

"Germans

seized the

children from

their mothers

and killed

them on the

spot," and

their mothers

and

grandmothers

were killed

two days

later.

b) An account similar to Dr. Meyer's is set forth in Rabbi Ephraim Oshry, The Annihilation of Lithuanian Jewry, Y. Leiman, translator (Judaica Press, 1995), pp. 195-196. He writes that women and children were driven into the forest on September 14, the Germans separated the children from the women, and shot the children," and on September 16th they shot the women. Rabbi Oshry adds that the details were provided by "Mrs. Yami of Visatz" who had "escaped from the women's camp."

c) In Lita, a letter is quoted from a nephew of Khaym Shoys, stating: "One late-summer day everyone was once again driven to the Ashmonishke forest {Vezaitines forest}. Here they separated children and the young from the elders."

d) Saliklis

states that

the first

killing

involved 100

women, young

girls, and

children. This

included

approximately

20 children,

from a baby on

up. The second

group, a week

later, was

more than 100,

including

children of

various ages.

Dr. Meyer's and Rabbi Oshry's chronology for September, in which the victims were taken to the forest together, after which the children were separated from their mothers and killed in the first September killing, seems inconsistent with the physical evidence in the Soviet report (assuming that each grave contained victims from a single day). The bodies of women and children were found together in the second mass grave, while "girls" (presumably young women) were found in the first. The physical evidence also seems inconsistent with Saliklis' testimony that the first killing included approximately 20 children, from a baby on up.

Thus there are

several

sources,

attributable

to the

survivor of

the second

day, that set

forth an

alternate

version of the

first day's

killings.

Instead of the

"girls" found

in the

exhumation of

the first

site, the

victims

consisted of

"children"

separated from

their mothers.

The mothers

had been

brought to the

forest too,

but not killed

until two days

later. The

word "girls"

means

adolescent

girls or young

women, and is

different than

the word for

"children."

The Saliklis

interrogation,

though it must

be viewed with

caution,

offers

evidence

independent of

Ms. Yami that

children as

young as a

baby were

killed on the

first day.

Saliklis

placed the

number of

these children

at 20.

If each

exhumed grave

contained

victims from

only one day,

the

exhumations do

not seem to

support this

alternate

version of

children

killed on the

first day.

How would Yami

(age 33 and

without

children)

learn of the

children

separated from

their mothers

on the first

day? Perhaps

she could have

been part of a

larger group

of women and

children

brought to the

forest on the

first day.

From this

group, perhaps

only the

children were

killed, and

the remaining

adults sent

back to

Anieleske.

Alternatively,

she might not

have been in

the forest

herself on the

first day, but

could have

heard of the

events from

one or more

women who were

brought back

to Anieliske

following the

killings on

the first day.

Saliklis said

there were two

deep graves

prepared for

the first day.

It is unclear

whether these

were adjacent.

The sources

describe one

version or the

other of the

events of the

first day,

without

attempting to

harmonize

them. If both

accounts are

accurate, what

was the

connection

between

transport of

the women with

their children

into the

forest, with

the transport

of young women

purportedly

taken for

labor? Were

they all

transported as

part of the

same group, or

were there

separate

selections and

transports for

the young

women, and the

mothers

together with

their

children? Is

it possible

that they were

transported to

different

sites? Is it

possible that

more were

transported to

the site than

would fit in

the

pre-prepared

graves, so the

mothers were

taken back to

Anelishke to

be killed two

days later?

Is it

possible that

the children

separated from

their mothers

on the first

day, were

buried in the

same grave as

those killed

on the second

day?

The most likely source of additional evidence would be the interrogation of Puzneckis concerning the first day's killings. His interrogation on the present site concerns the second day. See Interrogation at n. 6. At the time these interrogations were obtained by a researcher for this website, the first day's interrogation could not be located. However another search should be made. In addition, perhaps another researcher has a copy outside the archives. Puzneckis' testimony is largely consistent with the physical evidence with only one simple change: assume his memory placed the second day's killings at the site of the first killings. Such a mistake would be understandable for someone who participated in both. His testimony is also largely consistent with that of the priest present on the second day. Therefore Puzneckis' unknown testimony as to the first day is critical.

Further sourcing is also desirable as to alleged killings of some of the young children on June 23. It seems likely that the Ulm judgment, and not information provided by Yami, Shaus or Osher, was the original source of this information as later related in Yahadut Lita. Yami, Shaus and Osher had all provided infomation for the Gorzd Memorial Book (Yami's information was supplied through others). If the alleged killing of the young children on June 23 had been known to any of them, this information would have been included in the Gorzd Memorial Book and in the other Jewish accounts. Dr. Meyer also reports that the Yami told Liebke Shauss that the women did not believe after June 24 their husbands had been killed. Such disbelief seems unlikely if their infants and young children had already been seized from them on June 23.

The

conflicting

accounts could

indicate that

there are

further

undiscovered

grave sites

for children.

If the

information

from the mayor

of Gargzdai is

accurate,

there could be

an

undiscovered

site for those

children

killed on June

23. If the

information

from Dr.

Meyer, Rabbi

Oshry and/or

Saliklis is

accurate, then

either the

young children

and infants

killed on

September 14

would have

been buried

with the

victims of

September 16,

or there would

be an

undiscovered

grave site for

those young

children or

infants killed

on September

14.

There is a difference between the Ulm judgment and Yahadut Lita as to the children supposedly killed on June 23. The Ulm judment specifically says the killing of the young children took place on June 23, but does not tie it into the relocation of the women and children across the river. Yahadut Lita does not give the date but states the killing took place during the journey to the imprisonment site for the women and children. The reason for this difference in the two accounts is unknown.

The name of the customs official who received the information from the Mayor of Gargzdai is spelled as "Lach" in the book "KZ-Verbrechen vor deutschen Gerichten, Band II: Einsatzkommando Tilsit - Der Prozess zu Ulm"(Frankfurt am Mein: Europaïsche Verlagsanstalt, 1966), pp. 401-402. Lach is cited eleven times in the Judgment as a credible witness. An individual with a slightly different spelling is listed with occupation Customs Inspector in the Memel City Directory, 1942. See note following Part III above.

The Ulm judgment does not state when the conversation took place between the customs official and the Mayor, the source of the Mayor's information, or the number of links between the Mayor and anyone with first hand knowledge. Because neither the Gargzdai mayor, nor those reporting the information to him, were present in court, the information was at least double hearsay. German courts do not have the same prohibitions against hearsay which generally apply in American courts. Jeremy A. Blumenthal, "Shedding some Light on Hearsay Reform: Civil Law Hearsay Rules in Historical and Modern Perspective," 13 Pace Int'l Law. Rev. 93, 99 (2001); Thompson Reuters Practical Law, Legal Systems in Germany - Overview, 26. Rather than prohibiting hearsay testimony, the German court assesses the reliability of the information.

Here, the reliability might well be regarded as questionable. The information could have passed through any number of persons before reaching the Mayor.

The Nuremburg Tribunal also permitted hearsay testimony. Michaela Halpern, "Trends in Admissability of Evidence in War Times Trials: Is Fairness Really Preserved?" 29 Duke Journal of Comparative and International Law 103, 108-109 (2018).

_____________________________________________________________________________________________

The first

known

photograph of

either of the

killing sites

of the women

and children

was taken by

George Birman

when he

visited

Gargzdai in

April, 1945.

The photo may

be viewed

online at the

collection of

George Birman

papers the

United States

Holocaust

Memorial

Museum, Item

8, bottom

row, second

photo from

left.

In recent

years, a

considerable

number of new

sources have

appeared

regarding the

killing of the

women and

children of

Gargzdai.

Hopefully

further

revelations

will continue

to clarify

these tragic

events.

VI. Orders to Einsatzkommando Tilsit

The men's killing in Gargzdai is particularly important to historians of the Holocaust because it was the first in the Soviet Union. The source, timing and content of orders to Böhme concerning the first killings are the subjects of controversy.

The Memorial

to the Men's

killing is on

the west end

of Klaipedos

gatve

(Klaipeda

Street),

between a

retail store

to the west

and an

apartment

complex to the

east. A

photo

of the Men's

Monument is

on this

website.

The monument

erroneously

dates the

killings in

July, 1941,

rather than on

June 24.

Also on this

website is a German

aerial

reconnaissance

photo,

taken in

January, 1945,

obtained from

the U.S.

National

Archives,

which shows

the area of

the killing

site.

There are two

Monuments to

the killing of

the women and

children.

Both are in

the Vezaitine

Forest,

northeast of

Vezaiciai, on

Road 166

leading to

Kuliai.

Locations of

the monuments

are set forth

in the

Holocaust

Atlas of

Lithuania, Item

171

(southwestern

site) and Item

158

(Northeastern

site). The

location of

Vezaiciai and

Road 166 to

Kuliai may be

seen at the openstreetmap.org. As

of 2009, there

were separate

marked

entrances off

the east side

of Road 166

leading to the

two

sites.

The more

northeasterly

site is more

easily

located,

because there

is a direct

road from 166

to the

site.

The more

southwesterly

site is more

difficult to

locate, and a

guide may be

desirable.

Photos

of the Women's

Monuments are

on this

website.

VIII.

Discrepancy

between German

and Soviet

Records as to

Number of

Victims at

Men's Killing

Site

There is an apparent discrepancy between the German records and the Soviet report as to the number of victims at the men's site. This discrepancy was noted by Aleksandras Vitkus and Chaimas Bargmanas (Chaim Bargman), "1941 Secrets of the Massacre of Jews in Gargzdai Not Yet Fully Disclosed" (2016). (article in Lithuanian, .pdf format) (article in html format [access in google Chrome browser, right click for English translation]) (pictures and introduction to article in Genocide and Resistance). The Soviet report of the exhumation indicates there were 396 male victims. Vitkus and Bargman indicate that several Lithuanian witness statements in Lithuanian archives had estimated the number of male victims as 400, not 200 as stated in the Ulm trial records. They point to other discrepancies in the number of victims, both as to the men and as to the women and children. These discrepancies exist in comparing various sources with each other, and also in comparing with pre-war figures for the Jewish population.

The figure of

396 men may be

supported by

comments of

George Birman,

a former

resident of

Gargzdai, who

provided much

of the

material for

the present

site.

Mr. Birman

told the

author (long

before the

Soviet report

became

available)

that some

former

residents of

Gargzdai

believed the

German figures

were too low

in comparison

to the Jewish

population of

Gargzdai at

the time. He

did not

believe that

any men who

were in

Gargzdai at

the time of

the invasion

survived the

shootings.

The only

survivors were

those (like

Birman himelf)

who were not

in the town at

the time of

the

invasion.

On

the other

hand, the

figure of 200

men and one

woman adopted

at the Ulm

trial is set

forth in early

documents,

including the

Situation

Reports used

at the trial,

and the even

earlier

Report

from

Staatspolizei

Tilsit to

RSHA, July 1,

1941 (a

document which

was unknown at

the time of

the

trial).

The Ulm

judgment

points out

that the

figure of

approximately

200 victims at

the men's site

was supported

by seven

witnesses who

were not

defendants in

the case, as

well as the

written

Situation

Reports.

The judgment

states that

this number,

determined by

the Stapo and

the SD, was

confirmed by

Böhme to

Einsatzgruppe

A and to

Section IV of

the RSHA

(Reich

Security Main

Office), and

by Defendant

Hersmann

to Section III

of the RSHA.

The following

arguments may

support the

accuracy of

the figure:

While a few

defendants

contended the

number was

lower,

apparently no

one at the

trial

contended it

was higher.

Further,

although some

of the male

victims were

unmarried

adolescents or

had no family,

others had a

spouse and

several

children. For

example, an

account

submitted to

Yad Vashem

indicates one

family with a

husband, wife,

and five

children

who all

perished in

Gargzdai. It

would seem

that the

number of

women and

children would

be

substantially

higher than

the number of

males. The

ratio of men

to women and

children might

favor the

figure of 200

men, rather

than 396, in

relation to

the reported

number of

women and

children found

at the

exhumation of

the two sites

in the forest.

The

German

judgment

states the

Jewish

population at

the time of

the invasion

was between

600

and 700.

If the figure

of 200 men and

one woman

killed at the

men's site is

correct, then

adding the 454

women and

children found

at the two

women's sites

totals 655.

This figure is

within the

range of the

total Jewish

population set

forth in the

German

judgment, but

would leave

unexplained

the

discrepancy

between the

201 victims

stated in the

German

judgment, and

the 396 bodies

found in the

exhumation of

the men's

site.

It

is possible to

suggest highly

speculative

theories to

account for

the

conflicting

numbers.

Theory A: The

German figure

of 200 men was

only an

estimate, and

the actual

figure was 396.

Arguments in

favor:

Is

it numerically

unlikely that

shooting all

the men would

result in the

round number

of 200?

In light of

the

unprecedented

nature of this

first mass

shooting of

the war, is it

possible that

accidentally

or

deliberately,

no one kept an

exact count on

June 24?

During

the

trial, did

prosecution

testimony

naturally

converge on

the figures

set forth in

the written

Situation

Reports? No

one had an

incentive to

testify to a

higher figure.

Pretrial

interrogation

of witnesses

yielded

estimates of

between 50 and

300 victims. Tobin

(2013), p.

165.

Yidishe

Shtet

states

pre-holocaust

Jewish

population was

around 800,

which compares

with the

Soviet total

of 850 victims

found in

exhuming the

sites.

Lithuanian

witness

statements in

Lithuanian

archives,

noted by

Vitkus and

Bargman,

estimated the

number of

victims at

400.

Arguments

against:

Given the very

large number

of mass

shootings

throughout

Lithuania,

chance could

easily result

in an accurate

count at one

location being

an even

multiple of

100. It is

also possible

that the

perpetrators

decided in

advance to

kill 200

males. See

Jürgen

Matthäus,

"Operation

Barbarossa and

the Onset of

the

Holocaust," in

Christopher R.

Browning, "The

Origins of the

Final Solution

-The-Evolution

of Nazi Jewish

Policy,

September

1939-March

1942,"

University of

Nebraska Press

and Yad

Vashem, 2004,

p.254. Having

already

decided upon

this round

number, they

then included

among the

victims enough

younger

individuals to

reach it. The

victims

included a 12

year old boy.

Id. p.

254; J.

Matthaus,

"Controlled

Escalation: Himmlers

Men in the

Summer of 1941

and the

Holocaust in

the Occupied

Soviet

Territories,"

Holocaust

and Genocide

Studies 21,

no. 2 (Fall

2007), 218,

223.

Failure to

keep exact

records would

be

uncharacteristic

of SS

personnel

involved, and

other conduct

of

perpetrators

during the

Holocaust.

In pretrial

interrogation,

driver Kersten

gave a figure

of 200. Tobin

(2013), p.

148. There is

no apparent

indication he

was influenced

by the written

documents.

The

discrepancy

between an

estimate of

200 and a true

figure of 396

is too large;

someone would

have realized

that the

estimate was

too low. In

his reports

Böhme had no

incentive to

underestimate

and could not

have done so

to this great

extent.

No

pretrial

estimate given

to German

investigators

was higher

than 300. Tobin

(2013), p.

165. If the

true figure

was 396,

someone would

have provided

an estimate

higher than

300.

Some of the

Jewish

population had

left Gargzdai

as a result of

the 1939 fire,

which could

account for a

discrepancy

between the

prewar Jewish

population and

the number of

victims.

__________________________________________________

[Note: Encyclopedia Britannica lists an even larger figure of 800 Jews killed in Gargzdai on June 23 and 24. The source of this figure is not given. As of April, 2017, approximately two dozen other webpages now cite this same figure of 800.

The first source of this number may be a Wikipedia article, The Holocaust in Lithuania, which as of April 2017 reads: "Approximately 800 Jews were shot that day in what is known as the Garsden Massacre. Approximately 100 non-Jewish Lithuanians were also executed, many for trying to aid their Jewish neighbors." Wikipedia's footnotes for this assertion cite Porat, Dina (2002), "The Holocaust in Lithuania: Some Unique Aspects, in David Cesarini, The Final Solution: Origins and Implementation, Routledge, pp. 161-162, ISBN 0-415-15232-1, and MacQueen, Michael (1998), "The Context of Mass Destruction: Agents and Prerequisites of the Holocaust in Lithuania," Holocaust and Genesis Studies 12(1): 27-48. Neither source appears to contain either the 800 or 100 figure.

Perhaps the

figure of 800

is

a mistake

based on one

estimate for

the total

Jewish

population of

Gargzdai,

including

women and

children. The

Wikipedia

author may not

have realized

that the women

and children

were killed

several months

later.

The German

judgment, pp.

401-402,

contains a

brief

secondhand

statement that

Lithuanians

killed some

small children

from Gargzdai,

in a small

wooded area

adjacent to

Gargzdai, on

June 23. See

discussion in

Part V above.

The accuracy

of this

information is

questionable.

The statement in Wikipedia regarding the killing of 100 non-Jewish Lithuanians may refer to the massacre in Ablinga, a tiny village about 12 miles east of Gargzdai. See Section XI below.]

___________________________________________________

Theory

B:

The grave also

contains

Soviet troops

or NKVD border

guards who

died in the

battle of June

22, 1941

Arguments

in favor:

Prior

to the

executions on

June 24, the

Jewish men

were forced to

bury Soviet

soldiers who

had died in

the battle on

June 22. Dr.

Arunas Bubnys, Holocaust

in

Lithuanian

Province in

1941, p.

41.

The number of

Soviet troops

who died in

the battle is

unknown (Gargzdai

Area

Museum).

The Ulm

judgment

reports that

approximately

100 German

troops died in

the

unexpectedly

difficult

attack. The

battle lasted

15 hours.

(Konrad Kwiet,

Rehearsing

for

Murder: The

Beginning of

the Final

Solution in

Lithuania,

p. 6).

Were 195 dead

Soviet

soldiers or

NKVD border

guards buried

in the same

ditch as the

mass grave of

the 201 Jewish

victims, or in

an immediately

adjacent ditch

which was not

recognized to

be separate at

the time of

the

exhumation?

If

the dead

Soviet

soldiers are

not in the

same ditch or

an immediately

adjacent one,

where were

they buried?

German

reconnaissance

photo from

January, 1945

may show

several

ditches end to

end within the

killing site,

although it is

unclear

whether this

photo predates

the

exhumation.

Arguments

against:

This theory apparently finds no support in the German trial records, and may be contradicted by the following passage in the judgment:

"Die gefangenen Juden wurden bis zur Exekution mit verschiedenen Aufgaben beschäftigt. Einige mussten die herumliegenden Leichen der gefallenen Russen beerdigen. Andere mussten einen von den russischen NKWD-Soldaten angelegten Verteidigungsgraben zum Exekutionsgraben vertiefen und erweitern." KZ-Verbrechen vor Deutschen Gerichten, Band II - Einsatzkommando Tilsit - Der Prozess zu Ulm (Europaische Verlaganstalt, 1966), p. 101.

(The

Jews held

prisoner were

employed in

different

tasks prior to

the

execution.

Some had to

bury the

corpses of the

fallen

Russians which

were lying

about. Others

had to deepen

and widen a

defensive

ditch built by

the Russian

NKVD soldiers

into an

execution

ditch.)

If

half of the

bodies wore

military

uniforms, one

might expect

at least some

durable

remnants such

as boots,

metal buttons

and buckles to

remain visible

upon

exhumation,

and this fact

to be noted in

the Soviet

report. The

border guards

were members

of the NKVD

(predecessor

to the KGB);

some uniforms

of NKVD

frontier

guards are

pictured at armchairgeneral.com.

In

response, a

reader of this

site has

suggested that

the SS may

have foreseen

a need for

Soviet

uniforms to

use in future

commando

operations.

For example,

the capture of

Maikop in

August, 1942

was

accomplished

through the

use of 62

members of the

Brandenburger

Regiment

disguised in

NKVD uniforms.

A few months

later, some

Germans in

Soviet

uniforms

fought in the

Battle of

Stalingrad.

Geoffrey

Jukes, Stalingrad:

The Turning

Point

(Ballantine

Books, 1968),

p. 94.

Approximately

25 SS troops

wore US

uniforms

during the

Battle of the

Bulge, in Operation

Greif

organized by

Otto Skorzeny.

(According to

German

accounts,

compiled by

the US Army,

Soviet

reconnaissance

patrols

sometimes wore

German

uniforms. Small

Unit Actions

During the

German

Campaign in

Russia

(Department of

Army Pamphlet

20-269, 1953),

p. 22-23.) At

Gargzdai,

uniforms could

have been

removed from

the Soviets

prior to

burial, which

would prevent

their

identification

as military

personnel at

the time of

exhumation.

Another possibility is that the investigators realized that some of the bodies were military, but thought it unwise to put that fact into the report, as it was not in accordance with the political purposes of the exhumation. See Mark Harrison, "Fact and Fantasy in Soviet Records: The Documentation of Soviet Party and Secret Police Investigations as Historical Evidence," Warwick Economics Research Paper Series ISSN 2059-4283 (February, 2016).

Theory C: Soviet records from the time of Stalin's rule are not reliable enough to be given any credence. The figure of 396 should be disregarded.

Arguments

in favor:

There

are notorious

examples of

Soviet

manipulation

of alleged

fact-finding

to serve the

ends of

propaganda.

Best known is

the

investigation

of the Katyn

massacre

of

approximately

22,000 Poles.

Although the

perpetrators

were Soviets,

the Soviets

planted

evidence to

implicate the

Nazis.

An official

Soviet

commission in

1944 issued a

false report

stating the

killers were

the Nazis.

Criticisms

of the Soviet

Commission

which resulted

in the reports

and trials

regarding the

killings in

Lithuania are

set

forth in Alfonsas

Eidintas,

Jews,

Lithuanians

and the

Holocaust,

Trans. Vijole

Arbas and

Advardas

Tuskenis,

Vilnius:

Versus Aureus,

2003. See unsigned

review at

shtetlshkud.com,

p. 15.

For example,

the Commission

did not

distinguish

between Jewish

and non-Jewish

victims, a

motive of the

Soviets was to

discredit

certain

Lithuanian

individuals

including

emigres, and

some of the

convicted

individuals

may have been

innocent.

Cautions on the use of such Soviet records are set forth in Mark Harrison, "Fact and Fantasy in Soviet Records: The Documentation of Soviet Party and Secret Police Investigations as Historical Evidence," Warwick Economics Research Paper Series ISSN 2059-4283 (February, 2016).

Arguments

against:

As

to Gargzdai,

while the

Soviet reports

contain

propagandistic

language, and

downplay or

omit the fact

that the

victims were

Jews, it is

difficult to

see any

propaganda

value in

inflating the

number of

victims in a

report which

was given

little if any

publicity at

the time.

As

to the

reliability of

the Soviet

investigations,

see N.

Terry,

The

Einsatzgruppen

Reports,

paragraphs 20

and 21.

_______________________________________________________

Perhaps the Soviet archives contain further information (such as notes or data forming the basis for the report) which will eventually cast further light on the matter. Further information could emerge from Lithuanian archives or other sources. In the meantime, any input from readers would be welcomed.

IX. Did Jewish civilians take up arms against the invasion?

The supposed justification for the Gargzdai shootings, set forth in internal Nazi documents used in the Ulm trial, was that the Jewish population had resisted the German invasion. Operation Situation Report #14, dated July 6, 1941 stated: "In Garsden the Jewish population supported the Russian border guards in resisting the German offensive." The same language was set forth in the Report of Stapo Tilsit, July 1, 1941, a document unknown during the trial.

The Ulm judgment found that this resistance had never occurred:

Die Einwohner von Garsden einschliesslich der Juden beteiligten sich nicht am Kampf. Es wurden von der kämpfenden Truppe auch keine Zivilisten gefangengenommen. Auch lagen keine Leichen der Einwohner herum, aus deren Lage auf eine Beteiligung am Kampf hätte geschlossen werden können. Es wurde auch von den Kompanien dem II./IR 176 keine Meldung über eine Beteiligung der Zivilbevölkerung am Widerstand erstattet. Es war überhaupt an diesem Tag und später beim IR 176 und bei den ihm vorgesetzten Stellen nie von einer Beteiligung der Zivilbevölkerung, insbesondere der Juden, am Widerstand in Garsden die Rede.

KZ-Verbrechen vor Deutschen Gerichten, Band II - Einsatzkommando Tilsit - Der Prozess zu Ulm (Europaische Verlagsanstalt, 1966), p. 94 (italics in original).

"The inhabitants of Garsden including the Jews did not take part in the struggle. No civilians were taken prisoner by the fighting troops. Also no bodies of residents were found lying around, from whose position participation in the struggle could be determined. There were no reports from the companies of II [Battalion] / Infantry Regiment 176 of civilians participating in the resistance. Neither on the day of the invasion nor later was there any discussion in IR 176 or their forerunners regarding resistance by the civilians in Garsden, particularly Jews."

Contrary information appears in the Gorzd Memorial Book, translated on JewishGen:

Two young Jewish men, Mendl Man and Josef Osherovitz, who helped the small border garrison to resist the incoming German army were later found dead near a machine gun. The Hitlerists used the fact that young Jewish men fought against them; they staged a public trial against the men in the shtetl. They drove all of the Jewish men together on a side of the shtetl and told them to dig a grave for themselves. When the grave was finished, they carried out the sentence: for staging resistance to the German army, all of the men were sentenced to death by shooting

The

Destruction of

Our Town

Gordz, by

Rashel Oysher,

translated by Gloria

Berkenstat

Freund, p. 325

(Hebrew-

Yiddish

section).

A similar

account

appears in Yahadut

Lita.

Pinkas

Hakehillot

Lita,

citing

testimony from

Ms. Osher as

one of its

sources,

states

"Several Jews

participated

in the

resistance."

Ms. Oysher does not state the source of her information regarding Mendl Man and Josef Osherovitz. Three pages later, Ms. Oysher states: "Ruchl Yami-Gritziana, who until the end was with all of the women at the grave and survived by chance, later spoke about the tragedy of our Gordz Jews." Id. at 328. This sole survivor may have been the source of Ms. Oysher's information about Mendl Man and Josef Osherovitz. Can any reader of this site provide further information regarding sources used by Ms. Oysher?

Rachel Osher is pictured with the Gorzd Esperanto club here.

Josef

Osherowitz is

mentioned in

the Gorzd

Memorial

Book as a

soccer player

and actor.

pp.

120;

122

(Hebrew-Yiddish

section). The

Yad

Vashem Central

Database of

Shoah Victims'

Names

contains pages

of testimony

regarding two

individuals

named Joseph

Osherowitz in

Gorzd.

The one who

could be

described as a

"young man" is

Osherowic or

Usherovitz,

Josef or

Yosef, a

butcher, age

30, husband of

Rivka.

Mendl Man is

mentioned in

the Gorzd

Memorial Book

as a member of

the synagogue

choir and an

actor. p.

108 and List

of

Names;

p.

124

(Hebrew -

Yiddish

section). He

is listed in

the

Central

Database

as age 20, a

worker,

single, son of

Yaakov and

Roza.

A history of

the 61

Infantry

Division

states there

were reports

that civilians

had taken part

in the

Gargzdai

fighting.

Walther

Hubatsch, "Die

61.

Infanterie-Division

1939-1945,"

Dorfler in

Nebel Verlag,

p. 18. The

author states

these reports

were followed

by the police

execution, in

which the

fighting

troops of the

Division did

not take part.

If Jewish civilians openly took up arms against the invaders at the time of the invasion, they were legal combatants. The Hague Convention of 1907 provided:

The laws, rights, and duties of war apply not only to armies, but also to militia and volunteer corps fulfilling the following conditions:

To be commanded by a person responsible for his subordinates;

To have a fixed distinctive emblem recognizable at a distance;

To carry arms openly; and

To conduct their operations in accordance with the laws and customs of war.

In countries where militia or volunteer corps constitute the army, or form part of it, they are included under the denomination "army."

The inhabitants of a territory which has not been occupied, who, on the approach of the enemy, spontaneously take up arms to resist the invading troops without having had time to organize themselves in accordance with Article 1, shall be regarded as belligerents if they carry arms openly and if they respect the laws and customs of war.

Annex to the Convention Regulations Respecting the Laws and Customs of War on Land, Section I, Chapter I, The Qualifications of Belligerents.

These Articles were incorporated into the Geneva Convention of 1929. Article 2 quoted above also continues essentially unchanged in the 1949 Geneva Convention Relative to the Treatment of Prisoners of War, Article 4(A)(6).

A

number of

residents or

former

residents of

Gargzdai who

were elsewhere

in Lithuania

at the time of

the invasion

were

imprisoned in

the Kovno

Ghetto.

Many died

there due to

illness caused

by intolerable

living

conditions, or

were killed in

various

"Actions"

during which

residents were

selected for

execution.

Executions

took place at

the old forts

ringed around

Kovno: at

Fourth Fort,

Seventh Fort

and Ninth

Fort. The

ghetto was

liquidated in

1944, with the

males

transported to

Dachau and the

females

transported to

Stutthof.

Some in the

Ghetto tried

to hide in

underground

bunkers, but

most of the

hidden persons

died when the

Nazis set the

Ghetto on

fire.

Gorzd

Yizkor Book,

page 351

(Hebrew

Section),

posted at the

JewishGen

Yizkor Book

Project,

contains a

list of Gorzd

residents

killed in the

Kovno Ghetto

and in

concentration

camps, as well

as those who

fought in the

Lithuanian

Division or

fell in battle

at the front.

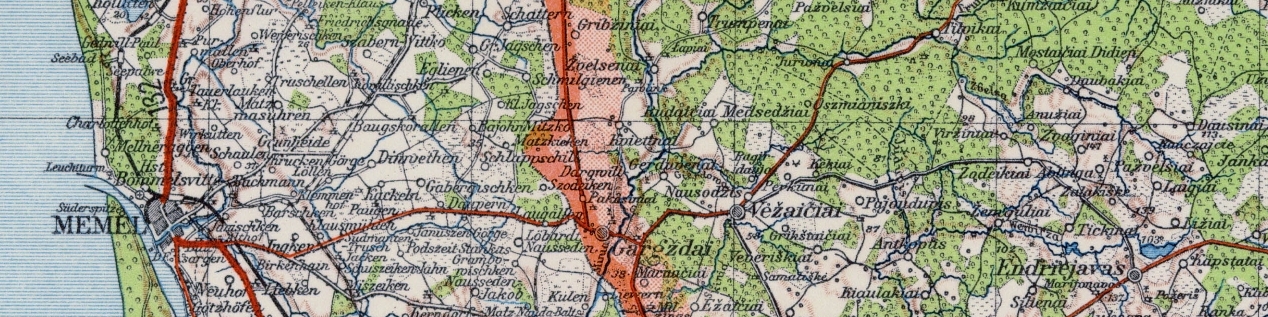

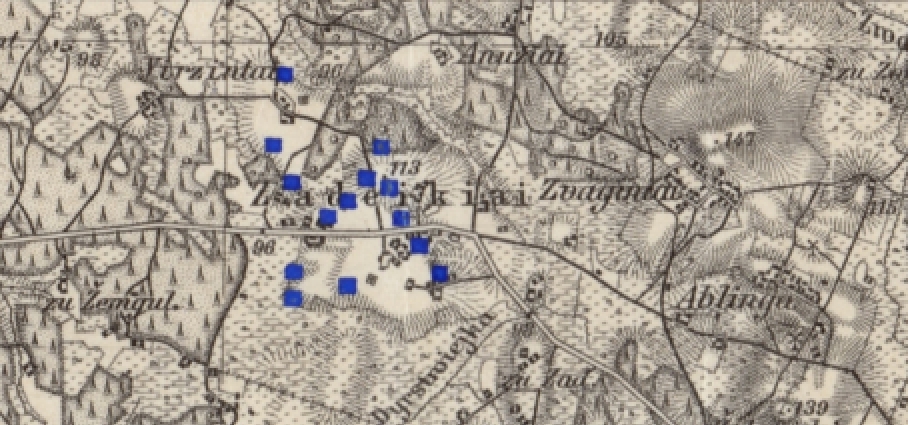

Maps showing Ablinga and Zvaginiai (Zwaginie) northwest of Endriejavas (Andrzejewo):

|

|

| Karte

des Deutschen

Reiches (1914) Sheet 4 - Paaschken Showing 14 dwellings in Ablinga and 15 in Zwaginie |

Lith.

Army ca.

1938 From Map 1301 at Lithuanianmaps.com |

Area

Between Memel

and

Endriejavas

Showing

villages of

Ablinga and

Zvaginiai

northwest of

Endriejavas

From R56 Tilsit, Ubersichtkarte von Mitteleuropa 1:300,000 (1939) at www.mapywig.org

While

the map below

appears to

show German

fortifications

near Ablinga

at the time of

the invasion,

it appears

that these

were in fact

Soviet

fortifications

under

construction.

See Rimantas

Zizas, Persecution

of non-Jewish

Citizens of

Lithuania,

pp.

24-25.

The blue color

is apparently

either an

error of the

map maker, or

a confident

prediction

that the

Germans would

quickly

capture them.

Gargzdai

main page

Aerial

Photo

of Gargzdai | Identification

of

Features on

Aerial Photo | Aerial

Photo of

Killing Site

Photos,

Page 2

(Women's

Memorials) | Photos,

Page 4 (Men's

Memorial)

This

page was

updated

September 3,

2021

Copyright © 2002-2021 John S. Jaffer