How to

Make Kehilalinks Pages

Introduction

In this lesson we will learn how to insert and manipulate pictures.

Pictures in web pages must be digital images. You can create digital

images in software, or by using a scanner or digital camera. You can

also copy images from other web pages, but remember that copyright

laws apply!

Image Files

Many beginning web page designers are surprised to learn that images

are stored in files that are separate from the text in a web

page. HTML has commands that tell browsers where and how to

display an image, but the computer data that actually makes up the

image is not HTML. Thus, one web page that has 100 different images

could consist of as many as 101 separate files.

The smallest unit of computer storage is called a "bit,"

which can have the values 0 or 1. All computer data,

including the letters in this sentence, are stored as groups of

bits. A group of eight bits is called a "byte." Most

measures of computer memory, file size, disk size, etc., is given

in terms of bytes, either thousands of bytes (kilobytes, or "K"

for short), millions of bytes (megabytes, or "M" for short), or

billions of bytes (gigabytes, or "G"). [Technically, and

originally, a kilobyte is 1024 bytes (210 bytes), a

megabyte is 1024 × 1024 bytes, etc. But many storage media vendors

and even several international organizations define a megabyte as

1000 × 1000 bytes, so no wonder we are all confused.]

Images that we see on our computer screen consist of small

colored dots, called "pixels." Typically, we refer to the size of

an image as "so many horizontal pixels by so many vertical

pixels," e.g., "800 by 300."  Each pixel,

however, depending on how many colors are in the image, can

potentially take up more than one byte of memory. If you

have a display that can show 256 colors, each pixel will require

one byte to store its color. If your display supports "high

color," each pixel will need 16 bits (2 bytes) to store its

color. If your display supports "true color," each pixel

will need 24 bits (three bytes) to store its color. Because

there are so many pixels in an image, and each pixel can take up

more than one byte, images can take up a lot of memory. For

example, a 100 by 100 image displayed in "high color" contains

10,000 pixels and could need 20,000 bytes (20K) of memory to

display -- and that's a pretty small image when you consider that

most screens today can display 1440 × 1080 or more pixels.

Each pixel,

however, depending on how many colors are in the image, can

potentially take up more than one byte of memory. If you

have a display that can show 256 colors, each pixel will require

one byte to store its color. If your display supports "high

color," each pixel will need 16 bits (2 bytes) to store its

color. If your display supports "true color," each pixel

will need 24 bits (three bytes) to store its color. Because

there are so many pixels in an image, and each pixel can take up

more than one byte, images can take up a lot of memory. For

example, a 100 by 100 image displayed in "high color" contains

10,000 pixels and could need 20,000 bytes (20K) of memory to

display -- and that's a pretty small image when you consider that

most screens today can display 1440 × 1080 or more pixels.

Image File Formats

When we view web pages, one of our concerns is how fast we can

download the web page from its server. Large images, you

have probably noticed, can take a long time to download.

Recognizing this, computer scientists have devised methods of

organizing and compressing the data in an image file so that it

takes fewer bytes to store and therefore can be downloaded more

quickly. These methods are referred to as "image

formats." The two standard image file formats that virtually

all web browsers can display are called "Graphics Interchange

Format" ("gif," for short) and "Joint Photographic Experts Group"

("jpg") format. There is also a newer format called "Portable

Network Graphics" ("png", for short), which is intended to replace

gif. Image formats other than gif and jpg (and png) may not be

displayable by all browsers.

The "gif" format (and "png" format) is commonly used for image files

that have relatively few colors and large areas of the same

color. The "jpg" format is used for photographs and other

images that have lots of smooth color gradations, called "continuous

tone images." For example, the green 100 by 100 image above

has 2 colors: green and black. The gif file takes less than 1K, but

the same image can take six times that much space if stored as a

"jpg" file! A photograph, on the other hand, that might take

20K if stored in jpg format, might be twice or three times as large

if stored as a "gif" file.So the choice of image format can greatly

affect the size of an image file.

Even using these formats, however, images can be huge. When

designing your web pages, try to reduce the size of each image

file as much as possible so your page will load faster.

Image Editing

Software

Composer can convert some formats, but not all, and no matter

what format your images are in you will want to be able to edit

them -- change the color or size, crop them, or make other

changes. To do these things you will need to use image editing

software. If you don't already have a program to do this, a

popular free graphics program for Windows is "Irfanview", or the

excellent Paint.NET.

Mac users have iPhoto, or can use the free, powerful (but

complicated to use) "Gimp", if iPhoto doesn't do the

trick. (Gimp also has a version that runs on Windows, if you don't

like Irfanview or Paint.NET.)

Be very careful if you install these programs. These are

free programs and the developers make money by getting sponsored

by other software vendors who try to get you to install their

software at the same time as you install the free ones. So you

will see a lot of confusing prompts to install other software,

most of which is probably ad-ware (unwanted advertising

software). Read every prompt carefully and be sure to un-check

boxes, or check them, as appropriate, so you only install the

program you want and not the other stuff. If you make a mistake,

don't worry. You can uninstall anything you installed but didn't

want. But it is an annoyance.

Unfortunately, we won't have time in this course to discuss how

to use image editing software. That topic would take another

6-week course, at least! Each program, however, has a "help"

feature and some have tutorials.

Obtaining Images

for your Web Page

You can get images from many sources, including clip art packages,

scanning, using a digital camera, creating them with graphics

software, and, of course, copying them off the web. Copying an

image off of another web page is very simple: When viewing a page in

your browser, right-click on an image (users of older Macs with

single-button mice might have to use Control-click) and select "Save

Image As..." (or "Save Picture As..." -- the actual words may be

different in different web browsers). Your browser will prompt you

to choose the name of the file and folder to save it in.

Try using the "Save Image As..." feature in your web browser by

copying the square green image from this page to your computer. Be sure to

save it in the same folder where you are keeping your assignments. This will be important later on

in this lesson when we learn to insert images into a page.

The Question of

Copyright

Before I jump into trying to explain the concept of copyright,

please be aware that I am not a lawyer and am not offering any legal advice.

If you have any legal questions at all on this topic, contact an

attorney and don't depend on anything I say here!

Because JewishGen is a U.S.-based non-profit (and its web servers

are physically located in the U.S.), it is subject to U.S. copyright

laws. Copyright is a legal concept that gives the creator of an

original work exclusive rights to it for some period of time. The

goal is to encourage the creation of new works by letting the

creators profit from them. Copyright applies to any original works

of authorship, including poetry, novels, movies, songs, computer

software, and many other things. Interestingly, even though

copyrights can expire, translations or compendiums of older works

are considered to be new works and subject to copyright. See the

U.S. Copyright Office "Frequently Asked

Questions" for more information.

For our purposes as Kehilalinks web masters, we have to be aware of

copyright laws whenever we want to use material that we did not

create ourselves. For example, pictures -- photographs, drawings,

and paintings -- whether on the web or printed, are subject to

copyright. JewishGen expects all Kehilalinks web masters to do their

best to respect copyright laws. See http://kehilalinks.jewishgen.org/documentation/Policy.htm#10

for the current JewishGen policy.

You'll note that JewishGen's policy is that it is your

responsibility to get permission for any copyrighted material. By

posting any material on your site, you are attesting that the

material either is not copyright protected, or else you have

permission. This means that JewishGen (usually) does not check the

material that you post. JewishGen has a written policy to follow in

cases where someone notifies JewishGen of a potential copyright

violation (http://kehilalinks.jewishgen.org/documentation/Policy.htm#15).

This happens from time to time.

Fair Use

Copyright law is very complicated (see for example http://www.copyright.gov/title17/), so I won't

attempt to summarize it further. Although I'm not a lawyer, however,

I know that it's frequently difficult to determine whether or not

material is under copyright, or copyrightable, or whether it

matters. Strictly speaking, one should always have explicit, written

permission to use copyrighted materials. But the strict rule isn't

always practical, or even realistic, and the decision about what

materials to use is frequently a judgement call.

Even if materials are under copyright, however, there's the doctrine

of "fair use", which permits limited use of copyrighted material without acquiring permission

from the copyright owner. The four factors used to

determine whether a particular use is "fair" are

- The purpose and character of the use, including whether such

use is of commercial nature or is for nonprofit educational

purposes

- The nature of the copyrighted work

- The amount and substantiality of the portion used in relation

to the copyrighted work as a whole

- The effect of the use upon the potential market for, or value

of, the copyrighted work

Fair use may apply

in the case of Kehilalinks pages because, among other things, we

want to use the materials for "nonprofit, educational purposes", but

you'll need to decide for yourself in each case. See http://www.copyright.gov/fls/fl102.html

for more about the fair use doctrine.

Use of Materials

from Archives and Other Sites

Many archives and web sites have policies that allow limited use of

materials that they control. Look or ask for the policy at each

archive or web site that has materials you want to use in your

Kehilalinks site. For example, for Google's policy concerning use of

materials from Google Earth and Google Maps, see this web page: http://www.google.com/permissions/geoguidelines.html.

Yad Vashem's policy can be found here:

http://www1.yadvashem.org/yv/en/about/terms_and_conditions.asp.

See this page for YIVO's policy: https://www.yivo.org/Rights-Reproductions.

One requirement all of these polices generally have in common is

"attribution" -- a credit line indicating the source of the

material.

Clipart on the Web

There are many web sites that offer free clipart or other images and

blanket permission to copy and use them. Be very careful, however, to download

only images and do not download any software when you visit

these sites. Some of these sites can be very aggressive

about installing toolbars and other add-ons that are really adware

or spyware. If a site asks you to download or install anything

other than an image file, just say "no" and look elsewhere.

If a site asks you to register, be very careful about giving up your

email address or other personal information. I generally just look

for sites that don't require any registration. Also, you might want

to have a pop-up blocker before you visit these sites because some

are not shy about popping ads up over and over again.

Search for "free clip art" on Google, and practice copying

images. As you will see, there is a cornucopia of free icons,

buttons, horizontal lines, and other images that are available on

the web. But be careful what sites you visit and what you do on

those sites.

Security

This is a good time to remind you that, before you ever surf the web,

be sure you have a good antivirus program and all the latest

security patches installed! Even Mac users need to take

heed of this, because the number of Mac viruses is increasing

rapidly. You might want to take a look at the US Computer Emergency

Readiness Team (US-CERT) web site (https://www.us-cert.gov/cas/tips/)

that has additional tips for non-technical computer users about how

to keep your computer secure.

Making Images the

"Right Size"

I said earlier that it is important to keep the size of images

relatively small so that your pages load quickly, so I want to give

you a few guidelines for sizing images that you will use in your

pages, no matter what image editing programs you use.

Width in Pixels

If you have images that are more than the width of a browser window,

the person looking at the page either has to increase the size of

the window or scroll to see the entire picture. If the image is

larger than that person's screen then all they can do is scroll. And

don't forget that large pictures will be a lot slower to download.

(A new consideration for web designers is that many people are now

surfing the web on their smart phones, which have small screens, but

that's probably not an issue for our Kehilalinks pages.) Consider

that a 5 megapixel camera takes pictures of size 2500x1700 or so,

which is a larger resolution than most people's screens can show

without scrolling, and the size of the resulting jpg file can be

over 2 million bytes, and you can see why it is important to reduce

the size of the pictures that you put on your web site.

Many programs let you adjust the size of an image in inches or

centimeters and the resolution of the image, expressed as "so many

pixels per inch (or centimeter)". You can calculate the total

number of pixels with some simple math: multiply the number of

pixels per inch (or centimeter) by the width in inches

(centimeters). For example, if your software says an image is 100

pixels per inch and 5 inches wide, you know that the image will be

500 pixels wide when displayed in your page. Similarly, if you scan

a 5-inch wide postcard and use a resolution of 100 pixels per inch,

the resulting image will be 500 pixels wide. It doesn't matter

whether you adjust the resolution or size of the picture to reduce

the number of pixels because web browsers generally just care about

the number of pixels.

Quality or Number

of Colors

In addition to reducing the number of pixels in an image, you can

reduce the size of the image file itself by increasing the

compression of the image. In gif and png files, you can reduce the

number of colors from 256 to a lower number. In jpg files you can

reduce the "quality" of the image. Your software may offer you

"low", "medium", and "high" as choices for jpg files, or numbers

ranging from 1 to 100, or even the choice of a percentage. The best

trade-off in jpg images for the web between size and quality occurs

at the "medium", or "70", or "70%" quality level. Higher qualities

can greatly increase the size of the image file without looking

noticeably better on the screen. When preparing your images for your

web site, use image editing software and experiment with different

quality settings to see what works best.

Inserting Images

Into a Web Page

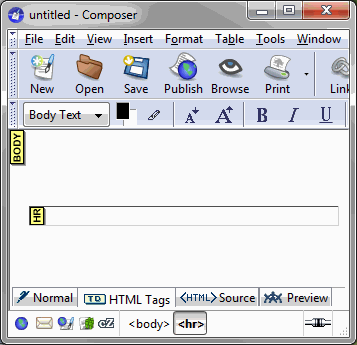

Before we learn to insert an image into a web page, first open a new

Composer window.

Before we do anything else, save the new page in the same

folder where you already saved the green box.gif file. It

is important for this lesson that the image files and the HTML files

are in the same folder. Technically speaking, this is not a

requirement for a web page, but if you have the image and HTML files

in the same folder it will make things easier for me to explain and

easier for you to follow my explanation.

To insert an image into your page in Composer, click in your

Composer window where you want to insert the image, then either

click on the "Image" icon  in the second

tool bar line or select

in the second

tool bar line or select

Insert ->

Image...

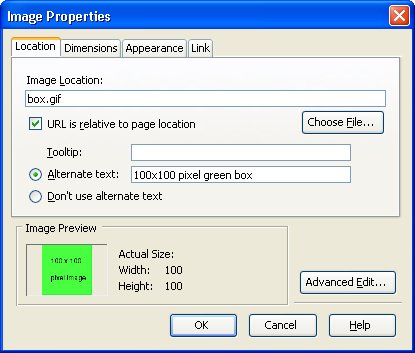

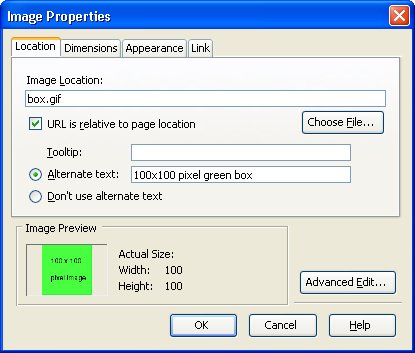

Composer will present you with a new window, called "Image

Properties." The first "property" that you want to choose is

the image file to insert. Click on "Choose File..." to tell

Composer the name of the file and the name of the folder it is in.

Find the "box.gif" file that you downloaded earlier. It should be in

the same folder where you just saved the Composer page that you are

currently working on. If you saved them both in the same folder,

after you choose the file your Image Properties window should look

like the one shown here, with the name of the file, "box.gif", in

the Image Location and the box checked next to "URL is relative to

page location". If there is anything else in the Image Location then

you probably did not save the image file and the HTML file in the

same folder, so try saving the image and the HTML files again.

Note that I have typed some words where it says "Alternate text".

Alternate text is what is displayed when, for some reason, the image

file itself can't be loaded, and sometimes when you let your mouse

hover over an image in a web browser (depends on the browser and on

the browser settings). You have the option of not supplying any

alternate text, of course, but it is a good idea to always do it.

Once you have correctly chosen the image file and typed in some

alternate text, click "OK" to insert the image into your web page.

Be sure to browse the page to make sure the page looks the same in

the browser as it does in Composer.

Copying and

Pasting Images

You might be tempted to simply copy and paste an image from

another web page or document into your Composer page. Don't do it.

Sometimes Composer will simply insert a link to the image on the

other site (what happens to your page when that site changes and

the image is no longer available?), or Composer may copy and place

the image in a temporary location that a browser can't access

(different versions of Composer have done different things).

Either right-click and save an image as a file on your computer or

copy and paste it into an image editing program, then save the

image as a file on your computer and insert it the way described

above.

Changing Image

Properties

Once you clicked "OK" to insert the image, the Image Properties

windows disappeared.  To get it back, double-click

on the image in Composer. You can also get to image properties by

clicking once on the image to select it and then selecting

To get it back, double-click

on the image in Composer. You can also get to image properties by

clicking once on the image to select it and then selecting

Format -> Image Properties

You can also

click on the image and then click on the Image icon on the

toolbar, and that will open the Image Properties window.

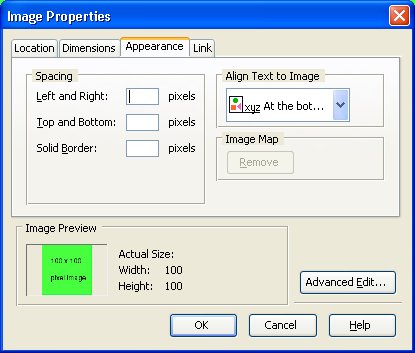

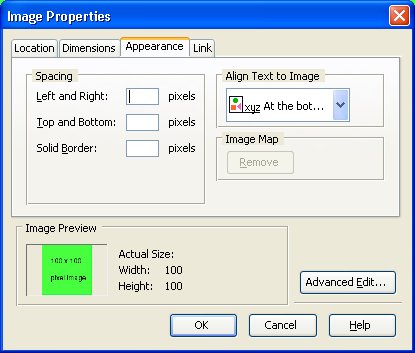

Now we'll learn about the two tabs "Dimensions" and

"Appearance" in the Image Properties window. The "Link" tab will

have to wait until we learn about HTML links in a later lesson.

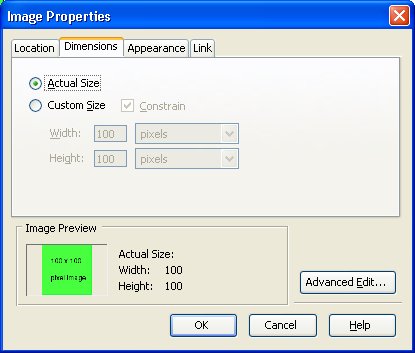

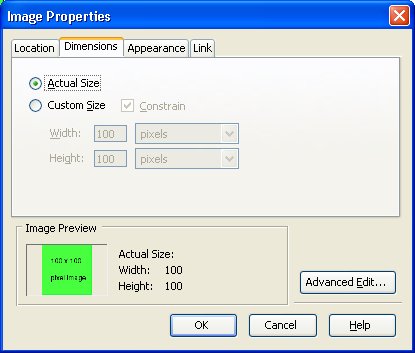

Dimensions Tab

Click on the "Dimensions" tab in the Image Properties window.

Your Image Properties window should look like the one here. The

image is "actual size" -- 100 pixels by 100 pixels. You can also

change the size of the image by clicking in the circle next to

"Custom Size" and choosing a new width and height. Here, for

example, is the exact same green box image file, but with the custom

size set to 20 x 20 pixels:  This doesn't change

the size of the image file itself, just the size as displayed in

the web page. So, if this was a really large image file, even

though I set the displayed custom size to be very small, it would

take just as long to load and take up just as much memory as if it

were displayed at its actual size.

This doesn't change

the size of the image file itself, just the size as displayed in

the web page. So, if this was a really large image file, even

though I set the displayed custom size to be very small, it would

take just as long to load and take up just as much memory as if it

were displayed at its actual size.

If you keep  "Constrain"

checked, you can only choose a combination of width and height that

have the same proportions. Because the original image is square, you

can only choose dimensions where the width and height are the same.

If you uncheck "Constrain", however, you can change the proportions

of the image, like here, where the image is 200 x 70: Again,

this doesn't change the original image, just the way it is

displayed. Be aware, however, that changing the proportions of an

image will also distort it. For example, the text in the green box

is much flatter in the 200 x 70 version than in the actual size of

100 x 100.

"Constrain"

checked, you can only choose a combination of width and height that

have the same proportions. Because the original image is square, you

can only choose dimensions where the width and height are the same.

If you uncheck "Constrain", however, you can change the proportions

of the image, like here, where the image is 200 x 70: Again,

this doesn't change the original image, just the way it is

displayed. Be aware, however, that changing the proportions of an

image will also distort it. For example, the text in the green box

is much flatter in the 200 x 70 version than in the actual size of

100 x 100.

You have a choice of making the size of an image "absolute" -- a

fixed a number of pixels -- or "relative" to the size of the browser

window. Try this out on the green box image by choosing a custom

size width of 100 and a height of 100, but make sure to uncheck the

"Constrain" box and select "% of window" instead of "pixels" for the

width. You should get something like this:

What happens when you adjust the size of

the window? The image should always occupy the full width -- 100% --

of the window no matter how narrow or wide you make it. Similarly,

you can make the image 50% of the window size and it will always

occupy exactly half of the width of the window.

What happens when you adjust the size of

the window? The image should always occupy the full width -- 100% --

of the window no matter how narrow or wide you make it. Similarly,

you can make the image 50% of the window size and it will always

occupy exactly half of the width of the window.

I recommend that you (whenever possible) use the actual size of an

image. The reason for this is that not all browsers treat the

modified size in the same way. If you make the image smaller,

for example, I have seen some browsers, instead of shrinking the

image, simply truncate it, cutting off the "excess" to make the

image fit the smaller space! When you make an image larger, on

the other hand, the browser has to increase the size of the pixels,

so that you end up with a picture that contains large squares and

looks blurry. In most cases when you need to modify the size of an image,

you are better off doing it with graphics software rather than

using the size property in a web page.

Appearance Tab

Now  open the Image Properties window for the box image and

select the "Appearance" tab. There are two key features here. First

of all, there are the parameters for "spacing". The "Left and Right"

open the Image Properties window for the box image and

select the "Appearance" tab. There are two key features here. First

of all, there are the parameters for "spacing". The "Left and Right" and "Top and Bottom" boxes refer to the

amount of empty space (in pixels) to leave around the image. This

feature is useful when you have text wrap around the image, to put

some blank space between the text and the image. (We'll learn about

wrapping text around an image soon.) The "Solid Border" allows you

to add a solid border around an image, like the 5-pixel border shown

around the green box here.

and "Top and Bottom" boxes refer to the

amount of empty space (in pixels) to leave around the image. This

feature is useful when you have text wrap around the image, to put

some blank space between the text and the image. (We'll learn about

wrapping text around an image soon.) The "Solid Border" allows you

to add a solid border around an image, like the 5-pixel border shown

around the green box here.

You can change the color of the

border around the image by selecting the image (i.e., click on it

once in Composer to highlight it) and then

You can change the color of the

border around the image by selecting the image (i.e., click on it

once in Composer to highlight it) and then

"Format -> Text Color".

(That's strange, I know, that the border around an image is treated

as text.)

Try making borders of different colors and thicknesses around the

green box in your practice page.

Composer offers a variety of options when it comes to text alignment

relative to an image. Some of the options treat the image as

if it was in-line with the text, allowing you to choose where the

text aligns with the image. Two other options anchor the image to

either the left or right side of the web page and allow the text to

flow around the image. For example, the "Image Properties" window in

this section uses the "Wrap to the left" alignment, which puts the

image on the right side of the page and allows the text to flow

around the left side of the image. The green boxes in this section

that have 5-pixel borders, on the other hand, uses the "Wrap to the

right" alignment.

Type a paragraph of text in your practice page (the one you already

have open that has the green box in it), then try inserting the

green box in the middle of the text someplace and try out different

alignments to see how they work. You can also "drag and drop" the

image, to move it around in the page. Try that out, especially with

the "Wrap to the left" and "Wrap to the right" alignments, to see

what happens. Try inserting two green boxes and moving them around

relative to each other. Also, don't forget to browse the page to see

how things look in different browsers and resize the browser windows

to see how the window size affects the placement of the images on

the page.

Note that not

all of the "alignment" options are supported by all browsers

(and even the ones that are supported are not guaranteed to work

exactly the same), but the two "wrapping" options generally work

the same in all browsers.

Centering Images

You can center an image by putting it in its own paragraph (i.e.,

using the "paragraph" format, or just separated from text by a line

break on top and bottom), clicking on the image to select it, and

then centering it by using the horizontal alignment tool.

Placing Images

Side-by-side

It isn't

possible to reliably put images side-by-side using the tools that

we've learned about up to now, so don't frustrate yourself

by trying. You'll add all sorts of spaces and line returns that

might look OK until you view the page in a different size window,

and that will mess up the layout of the text. We will, however, in a

future lesson, learn a technique for laying out pictures in a

controllable way -- above, below, side-by-side -- that will persist

even when browser windows are different sizes. Please be patient,

neither Rome nor our web pages can be built in a day!

Horizontal Lines

Horizontal lines help to break up a web page, visually separating

different sections. You can draw lines using an HTML feature or use

an image. You will find many line images on the clip-art sites, or

you can even use a single-pixel image and change the dimensions of

the image to create a line. This is a line image that I copied off

the web:

Single-pixel

Lines

Although in general I say that you should always use the

original size of an image, there are some cases when using

different height and width dimensions can help speed the

downloading of your page. For example, you can use a

one-pixel image, which downloads extremely fast, but specify a

height of 3 pixels and a width of 100% of the window for the

image dimensions, to create a color bar in your web page. You

can use an image editing program, like Irfanview or Gimp, to

create lines or single-pixel images in whatever colors you want.

Here's a single-pixel red gif file (that I made using Irfanview)

displayed as a 500x3-pixel line:

Right-click the red line and

download the "redpixel.gif" file using "save image as". It

can be a bit tricky to right-click on the line because it is

only 3 pixels tall. Use the redpixel.gif file to make your

own color line.

Be

careful to specify the dimensions of the line right at the

time when you insert the single-pixel image. If you

forget, it could be very, very hard to find and edit the

misplaced, tiny pixel image! Can you see the red

pixel just after this sentence? -->

<-- How easy is it for you to

right-click on it?

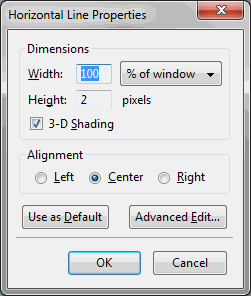

HTML Lines

HTML has a feature that will draw horizontal lines that do not

require a separate image file. Think of them as a relatively

"cheap" (in the sense that they don't cost much in the way of

download time and computer memory) type of image. They are a

relatively simple web page feature, so you can also think of this

part of the lesson as relatively cheap (also in terms of time and

memory -- your own).

The exact appearance of HTML horizontal lines will vary by

browser. Character-based browsers will display them as a

line of dashes or underscores, while graphical browsers will show

them as either solid or shaded lines. They are always gray or

black. Composer gives you some simple controls over how they

will look.

100%

window width, 2 pixel height, centered, 3D shading

50%

window width, 5 pixels height, centered, no 3D shading

To insert an horizontal line into your document, select

Insert -> Horizontal Line

This will draw a simple line using default settings, wherever the

blinking cursor is. Composer will put line breaks immediately

before and after the line. To set a horizontal line farther apart

from text, insert extra line breaks before and after the line.

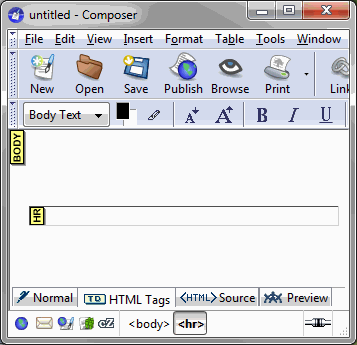

Selecting HTML

Lines

HTML lines are usually quite thin and difficult to select, but you

need to be able to select them so you can delete them or change

their properties. An easy way to select a horizontal line is to

click on the "HTML Tags" tab at the bottom of the Composer window.

You will see a yellow "HR" next to the suddenly wider horizontal

line. Click on the line (or the yellow "HR") to select the line.

You can then press the "delete" key or the "backspace" key on your

keyboard to delete the line, or double-click on the line to access

the Horizontal Line Properties window.

(Hint: This technique also works for the single red pixel you had

trouble right-clicking on earlier!)

Formatting HTML

Lines

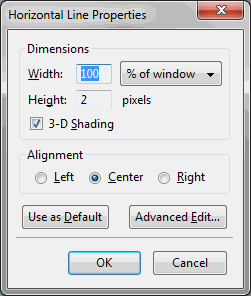

To format a horizontal line, double-click on it, which will open a

small window called "Horizontal Line Properties."

The properties of a horizontal line that you can choose are the

height and width, alignment, and 3-D shading. No colors are

possible in HTML lines. To make a color horizontal line you will

have to use an image, as described above.

Once you have set the properties of a horizontal line, you have

the option of making your settings the default, so that subsequent

horizontal lines that you insert will automatically look the same.

Height and Width

The height and width properties are similar to those you used for

images. You can set the width in pixels or percent of the wind ow. Height you can only set in pixels.

ow. Height you can only set in pixels.

Alignment

The three choices of alignment are left, center, and right.

The effect of these choices is identical to the effect of using the

paragraph alignment tool.

3-D Shading

The default graphical display of HTML horizontal lines in most

browsers is usually with some kind of shading to give the line a

chiseled or embossed look. Unchecking this setting may have

different results when the line is viewed in different browsers. In

some browsers it may be displayed as a solid, black line, while in

others it may look more like a box, with a black outline but nothing

in the center. Try this out with your various browsers.

Assignment

Your

assignment this time is to add images to your page. At a minimum,

add the Kehilalinks logo, which Kehilalinks policy requires on every

page. You can get it from any Kehilalinks page on the Kehilalinks

site. Download that image file to your computer (into the same

folder as your web page) before you insert it.

Also add a horizontal line, either an HTML line or a color line.

If you have pictures from your Kehila, add those, too. But make sure

they aren't too large!

I've added the Kehilalinks logo, a horizontal line image, and a

picture of Kamen Kashirskiy to my web page: kc-3.html.

I put the Kehilalinks logo in the rectangle in the top left of the

page. To insert the image (or text, or anything) into the empty

rectangle, in Composer

first click in the box so that the blinking cursor is there, then

insert the image.

Note that I used

an image for the horizontal line. I tried using a HTML horizontal

line, but there appears to be a bug in Composer when using an HTML

line in some cases, and I had trouble inserting text after the

HTML line,

so I went with the image line instead.

Copyright © 2009, 2010, 2012, 2013, 2014, 2016 Mark

Heckman. All rights reserved.

Each pixel,

however, depending on how many colors are in the image, can

potentially take up more than one byte of memory. If you

have a display that can show 256 colors, each pixel will require

one byte to store its color. If your display supports "high

color," each pixel will need 16 bits (2 bytes) to store its

color. If your display supports "true color," each pixel

will need 24 bits (three bytes) to store its color. Because

there are so many pixels in an image, and each pixel can take up

more than one byte, images can take up a lot of memory. For

example, a 100 by 100 image displayed in "high color" contains

10,000 pixels and could need 20,000 bytes (20K) of memory to

display -- and that's a pretty small image when you consider that

most screens today can display 1440 × 1080 or more pixels.

Each pixel,

however, depending on how many colors are in the image, can

potentially take up more than one byte of memory. If you

have a display that can show 256 colors, each pixel will require

one byte to store its color. If your display supports "high

color," each pixel will need 16 bits (2 bytes) to store its

color. If your display supports "true color," each pixel

will need 24 bits (three bytes) to store its color. Because

there are so many pixels in an image, and each pixel can take up

more than one byte, images can take up a lot of memory. For

example, a 100 by 100 image displayed in "high color" contains

10,000 pixels and could need 20,000 bytes (20K) of memory to

display -- and that's a pretty small image when you consider that

most screens today can display 1440 × 1080 or more pixels.

in the second

tool bar line or select

in the second

tool bar line or select

To get it back, double-click

on the image in Composer. You can also get to image properties by

clicking once on the image to select it and then selecting

To get it back, double-click

on the image in Composer. You can also get to image properties by

clicking once on the image to select it and then selecting This doesn't change

the size of the image file itself, just the size as displayed in

the web page. So, if this was a really large image file, even

though I set the displayed custom size to be very small, it would

take just as long to load and take up just as much memory as if it

were displayed at its actual size.

This doesn't change

the size of the image file itself, just the size as displayed in

the web page. So, if this was a really large image file, even

though I set the displayed custom size to be very small, it would

take just as long to load and take up just as much memory as if it

were displayed at its actual size. "Constrain"

checked, you can only choose a combination of width and height that

have the same proportions. Because the original image is square, you

can only choose dimensions where the width and height are the same.

If you uncheck "Constrain", however, you can change the proportions

of the image, like here, where the image is 200 x 70: Again,

this doesn't change the original image, just the way it is

displayed. Be aware, however, that changing the proportions of an

image will also distort it. For example, the text in the green box

is much flatter in the 200 x 70 version than in the actual size of

100 x 100.

"Constrain"

checked, you can only choose a combination of width and height that

have the same proportions. Because the original image is square, you

can only choose dimensions where the width and height are the same.

If you uncheck "Constrain", however, you can change the proportions

of the image, like here, where the image is 200 x 70: Again,

this doesn't change the original image, just the way it is

displayed. Be aware, however, that changing the proportions of an

image will also distort it. For example, the text in the green box

is much flatter in the 200 x 70 version than in the actual size of

100 x 100. What happens when you adjust the size of

the window? The image should always occupy the full width -- 100% --

of the window no matter how narrow or wide you make it. Similarly,

you can make the image 50% of the window size and it will always

occupy exactly half of the width of the window.

What happens when you adjust the size of

the window? The image should always occupy the full width -- 100% --

of the window no matter how narrow or wide you make it. Similarly,

you can make the image 50% of the window size and it will always

occupy exactly half of the width of the window. open the Image Properties window for the box image and

select the "Appearance" tab. There are two key features here. First

of all, there are the parameters for "spacing". The "Left and Right"

open the Image Properties window for the box image and

select the "Appearance" tab. There are two key features here. First

of all, there are the parameters for "spacing". The "Left and Right" and "Top and Bottom" boxes refer to the

amount of empty space (in pixels) to leave around the image. This

feature is useful when you have text wrap around the image, to put

some blank space between the text and the image. (We'll learn about

wrapping text around an image soon.) The "Solid Border" allows you

to add a solid border around an image, like the 5-pixel border shown

around the green box here.

and "Top and Bottom" boxes refer to the

amount of empty space (in pixels) to leave around the image. This

feature is useful when you have text wrap around the image, to put

some blank space between the text and the image. (We'll learn about

wrapping text around an image soon.) The "Solid Border" allows you

to add a solid border around an image, like the 5-pixel border shown

around the green box here.  You can change the color of the

border around the image by selecting the image (i.e., click on it

once in Composer to highlight it) and then

You can change the color of the

border around the image by selecting the image (i.e., click on it

once in Composer to highlight it) and then

ow. Height you can only set in pixels.

ow. Height you can only set in pixels.