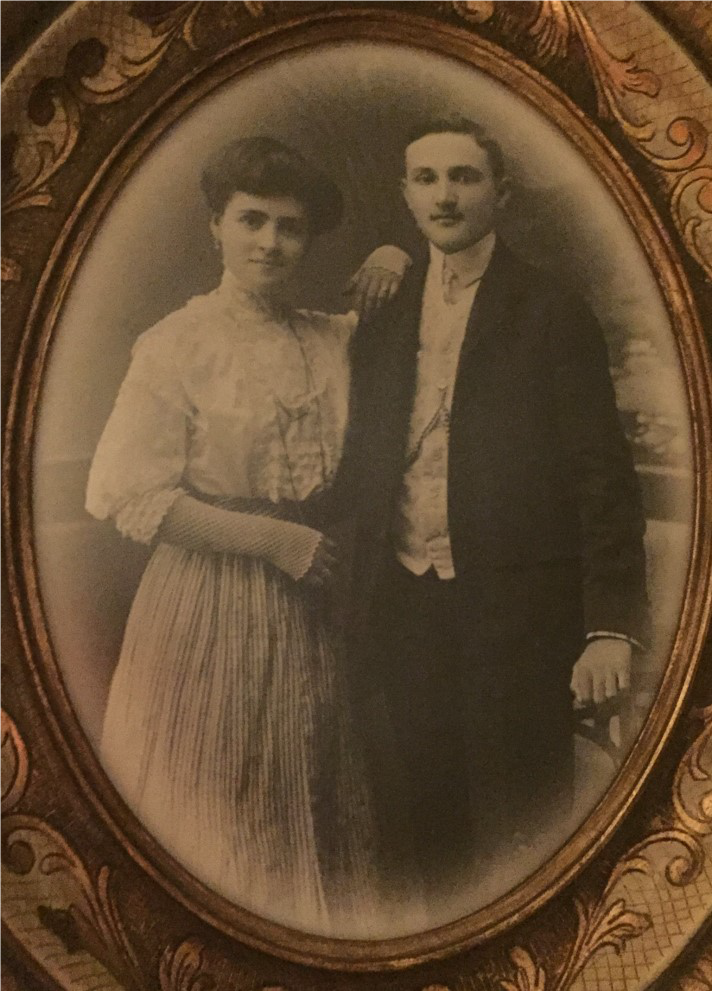

Irene's brothers, Ernest (left) and Arnold, were burned to death on the Eastern front.Irene and Eugene were born five miles from each other in a province then called Subcarpathian Ruthenia. Irene was born in Komlos (Chmil'nyk). Eugene was born in Komyat (Velikiye Komyaty). Eugene's paternal ancestors, beginning with patriarch Mark Leibovitz, had lived in Komyat since at least 1728; on his mother's side, some came from Nitra, now in the western part of the Slovak Republic. Subcarpathia was Austro-Hungarian through WWI. Then it was in the Slovak part of Czechoslovakia. Hungary retook the province in 1939. After WWII, it became part of the Soviet Union, the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic. Now it's in independent southwestern Ukraine, in a province called Zakarpattia.

Lili, Irene, and Elizabeth MermelsteinSome of Irene and Eugene's relatives left Europe between WWI and WWII. Eugene's cousin Hannah Senesh, a Palestine Mandate poet and spy originally from Budapest, parachuted behind German lines to help save the Hungarian Jews. The Hungarians captured, tortured, and shot her dead at age 23. Reinterred in 1950 in Mt. Herzl's military cemetery in Jerusalem, hundreds of thousands lined the streets for her funeral procession. Four of Irene and Eugene's uncles moved to America and had children. Had they remained in Europe, they probably would've been murdered because of their faith. Steve Lawrence, Eugene's first cousin, was born Sidney Liebowitz in 1935 in Brooklyn, U.S.A. Steve married Eydie Gormé. Together they were American singing sensations. Regulars on the Ed Sullivan Show, Steve and Eydie performed with the likes of Frank Sinatra, who always credited Steve as the greatest singer he'd ever heard. A younger generation of fans might recall Steve as Maury Sline from the 1980 Blues Brothers movie or as Morty Fine, Fran's father's voice from TV's The Nanny. Eugene's first-cousin Sheldon Mermelstein, married to Fran Greher, was born in Brooklyn in 1944. A long-time Manhattan Lower East Sider, Sheldon retired as the Director of Investigations at America's largest socialservices agency, the New York City Human Resources/Department of Social Services Administration. Fran retired as the Preschool Director of the Rosenbaum Yeshiva of North Jersey. Irene's first cousin Milton Mermelstein, from Newark, New Jersey, was an intelligence officer on a U.S. warship that landed with the first wave at Utah Beach on D-Day. An esteemed New York City lawyer, he became chairman of board of the Alexander's Department Stores. Though Jewish, his passion was Catholic charities. He received an honorary doctorate from New York City's St. John's University, a Vincentian institution that teaches how to find God and oneself in public service. A leader of the Knights of Malta, Milton was knighted by the Pope. Seymour (Cy) Mermelstein, another of Irene's first cousins from Newark, New Jersey, fought in WWII with the Devil's Brigade. This 1800-man unit, 463 of whom died in combat, killed some 12,000 German soldiers and captured another 7000. The Devil's Brigade was featured in books, TV, and movies (Devil's Brigade (1968); Monuments Men (2014)). In 2013, the Devil's Brigade received the Congressional Gold Medal. The Speaker of the House called Cy and his comrades-at-arms "the finest of the finest." Cy also helped liberate Germany's Buchenwald Concentration Camp, where the Nazis crucified priests upside down.

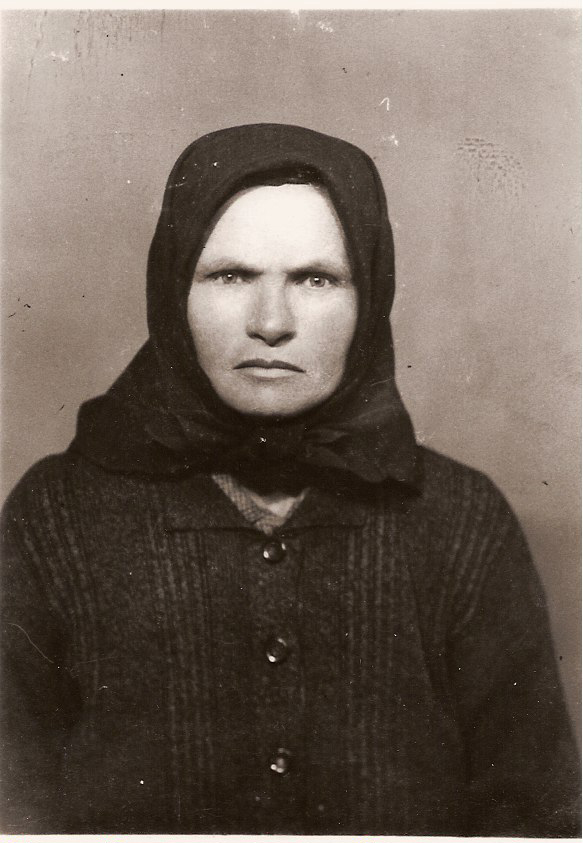

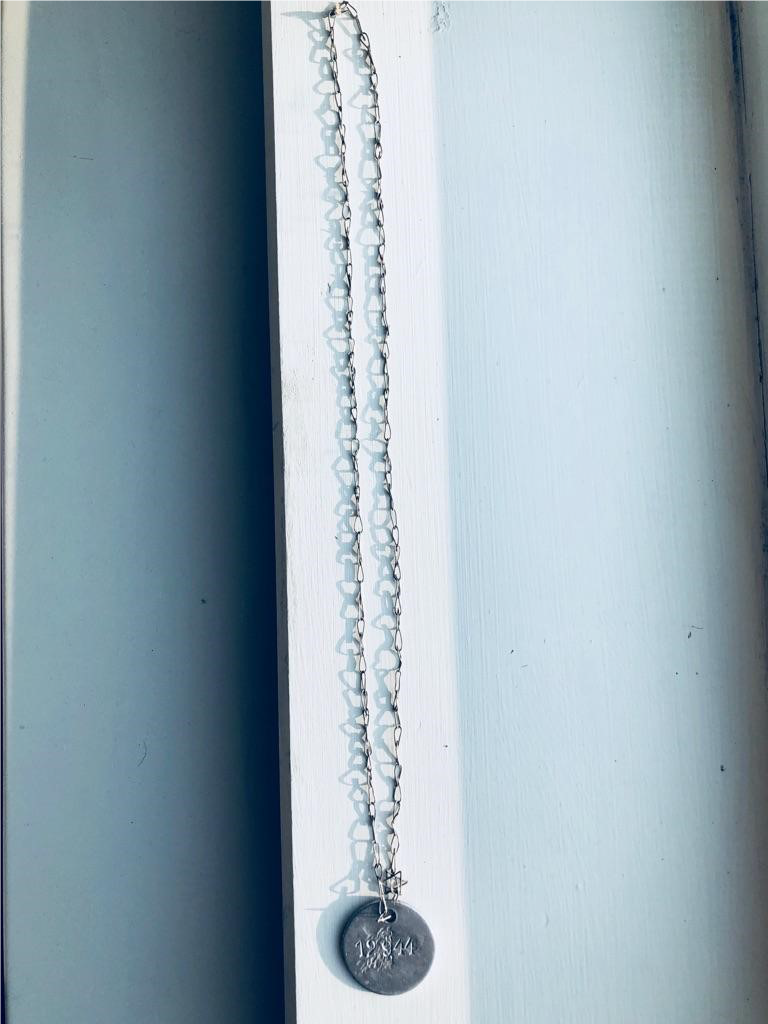

Above, a dog tag Irene Mermelstein wore while in slave labor at the Lorena factor. One side was inscribed with her number, on the other she engraved her nickname, Maca. Right, Irene after liberation550,000 American Jews fought in WWII. 38,338 died. 52,000, including Milton and Cy, earned military honors. For these GI Jews, fighting the Germans was a personal affair. So was defending America, their home. Unlike the handful who escaped to America, most of Irene and Eugene's relatives remained in Europe. The Holocaust destroyed their world. In 1922, Eugene's family moved from Komyat in the newly formed Czechoslovakia to Satmar (Satu Mare) in Northern Transylvania, Romania, because Benjamin Lebovits, Eugene's grandfather, was murdered by two Ukrainian brothers who owed him money. Everyone knew who did it. The authorities did nothing. The Hungarians retook Satmar from the Romanians in 1940 in a deal Hitler imposed on Romania. Eugene was drafted into the Hungarian Labor Battalions in October 1942. It was slave labor enforced by military discipline. He heard that his Battalion was going to the Eastern Front. No Jew who went was ever heard from again. Eugene escaped in September 1943. He was lucky. The German and Hungarian armies used the Jewish Battalion slaves as human mine sweepers. Two of Irene's brothers, Dr. Arnold Mermelstein, a lawyer, and Dr. Ernest Mermelstein, a dentist, both Battalion slaves, lived through the mines but perished on the Eastern Front when the Nazi SS or the Hungarians locked them inside a barn and burned it down. Arnold and Ernest were married. Their spouses, Ettu and Rachel, survived the camps and moved respectively to Israel and Canada after the war. Eugene eluded the fate of Irene's brothers by hiding in Budapest in September 1943. The Hungarians put a price on his head for de-sertion. His face was on wanted posters. And Budapest was unsafe. The Hungarian Arrow Cross fascist militiamen - the Nyilas - spent their days lynching Jews from lampposts and shooting 20,000 of them into the Danube. One day, Eugene wore a monogrammed shirt with his real initials on it. Another Jew caught him and demanded hush money. Eugene refused, saying, "You're a Jew. You'll never turn me in." But he did, and Hungarian counterintelligence arrested Eugene. Eugene was imprisoned and tortured in the Buda Castle, the Gestapo headquarters, and then turned over to the Hungarians for a court-martial show trial. He was tried in Kolosvar (Cluj) for desertion before Hungarian military judges, who sentenced him to death by firing squad. By day during the trial, the firing squad was practicing in the courthouse yard. By night, Jews, including Eugene's family, held candlelight vigils outside his prison. Three months before the near-total annihilation of the Northern Transylvanian Jews, the rabbis and the governing Jewish Council placed a tax on every relatively rich Jewish family in three cities to bribe Hungarian Col.-General Lajos Veress de Dálnok, the Deputy Regent of Hungary, to commute Eugene's sentence. Redeeming Jewish captives is a religious commandment called pidyon shvuyim. Izrael Lieb Berko, later martyred in Auschwitz, collected the bribe to save Eugene. (Izrael's grandson is a Legal Aid Society lawyer in New York City.) The court resentenced Eugene to 10 years' hard labor. Eugene didn't complete his sentence. He escaped from hard labor after a few months and hid for a few months on the estate of Count János Esterházy, a righteous gentile. By then the Soviets had liberated the area. But the Soviets captured and jailed Eugene in Debrecen, Hungary, pending his deportation to Siberia as a stateless person. Eugene talked his way out of jail after two months by befriending the prison's Soviet commanding officer, a Jewess.

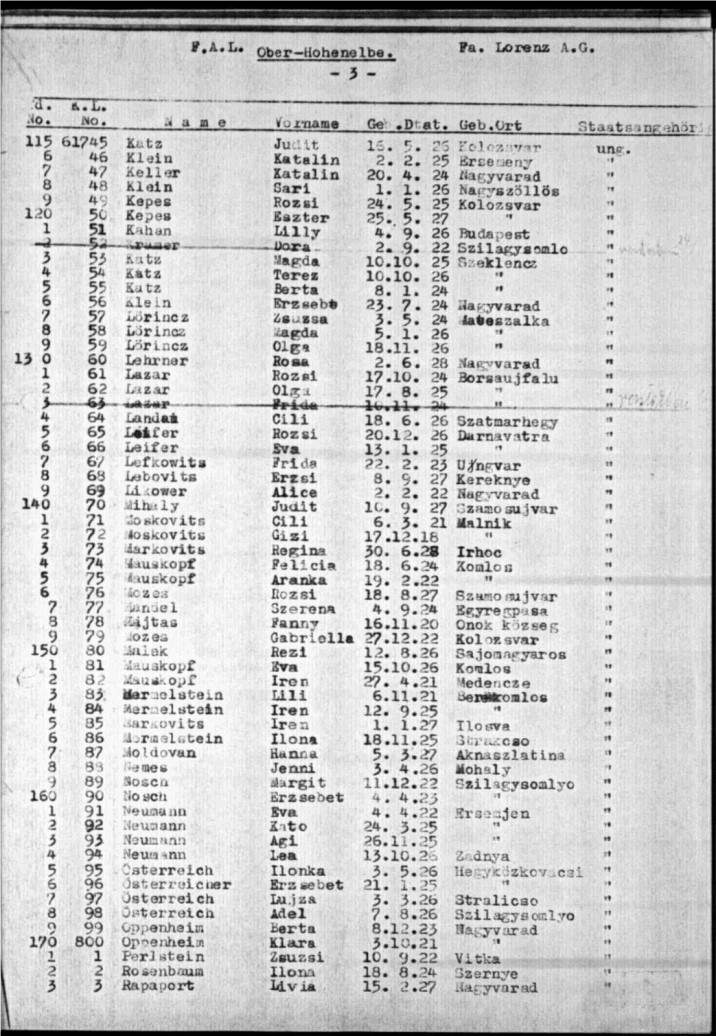

Irene and Lili's train transport from Auschwitz II-Birkenau to Lorenz on September 12, 1944, Irene's 19th birthdayEugene's return to Satmar was punctuated with the knowledge that most people he knew were now dead. Eugene's mother Toba, father Zoltan, and sister Katie were deported to Auschwitz in May 1944 and murdered. Eugene's brother, Carol, went to Melk, a Mauthausen Concentration Satellite camp, to dig tunnels in an extermination-through-work program. Carol complained about a kapo's cruelty to Jews. To avenge that slight, the kapo, a Jew from Satmar named Spitz, beat Carol to death in front of other inmates. A memorial with Carol's name on it is all that's left of him. Eugene was the only member of his immediate family who survived the Nazis and their collaborators. As badly as Eugene suffered, Irene suffered more. In 1941, the Hungarian police arrested 20,000 Subcarpathian Jews - Irene and Eugene's neighbors - on the pretext that they were aliens. They were handed over to the Ukrainian Auxiliary Police and the Einsatzgruppen, the German mobile killing units, who shot them into pits in Kaminets-Podolsk over three August days. It was the Holocaust's first industrial-scale murder. Irene attended a Ukrainian-Hungarian gymnazium, a high school that prepares students for university. She had to quit school at age 14. Hungarian law forbade Jews to attend school. But things got worse. In April 1944, Irene and her family were arrested and herded into two of Subcarpathia's 17 Jewish ghettos. A month later, Irene and her entire immediate family, together with 90,000 other Jews, were deported to Auschwitz II–Birkenau from an obscenely teeming and filthy brick factory in Munkachevo that served as a ghetto. (Among those in that factory awaiting deportation was Israeli actor Gal Godot's grandfather, Abraham Weiss, who survived Auschwitz.) Irene's sister Lili met a young dentist, Dr. Harry Katz, on the three-night train ride to Auschwitz. They fell in love in their cattle-car. Gassed and cremated the day they arrived in Auschwitz were Irene's mother Rose; father Ludwig; and one-year-old Leah, Edmund and his wife Matilda's baby. (The Zyklon B (hydrogen cyanide) gas that killed them was made by the same company that made Bayer Children's Aspirin.) The story of Leah's murder is told in Matilda's sister Gaby Kramer's book, Andor Kept His Promise from the Grave (2006). The SS transferred Edmund and Harry to Gross Rosen and from there to other camps. Edmund escaped during a death march by rolling down a mountain and was liberated in April 1945 by American troops in Plauen, Germany. Inside Auschwitz, Irene was marching one day with Lili and Elizabeth, her two sisters, when the SS told her to take a path away from her sisters. Dr. Joseph Mengele, the angel of death, stood guard at this selection. He beat with his riding crop anyone voicing discontent. But he granted Irene's plea to go with her sisters. Irene says it was because she was blond with blue eyes and thus to Mengele not a Jew. That's how the three sisters went to Birkenau, taking the path now traversed in the annual March of the Living at Auschwitz as Israeli fighter jets scream overhead.

The Mermelsteins brothers and sisters: Alex, Lili, Irene, Elizabeth, and Edmund

Irene on her 93rd birthdayElizabeth's first husband, Dr. Eugene Klein, a lawyer, was deported to Auschwitz and never heard from again. In Satmar after the war she remarried blond and blue-eyed Joseph Zelig, whose first wife and two sons were murdered. Joe, hiding in Budapest during the war, lived in the Swiss embassy and worked with Swiss Vice -Counsel Carl Lutz, who saved 62,000 Jews. Eugene courted Irene. On September 11, 1945, they married in Satmar. Irene would turn 20 the next day; Eugene had turned 24 five weeks earlier. They had a daughter, Agi, named after Irene's best friend, who never returned from the camps. Lili married Harry upon their liberation. Many Jewish survivors after the war tried to go Mandate Palestine to break the British blockade, in place until Israel's independence in 1948. As a Siguranța agent and smuggler, Eugene was in charge of a few hundred displaced Jews who traveled from Hungary through Romania on their way to sail to Palestine as part of the Aliyah Bet movement. He also saved the remnants of Irene's family, including Lili, Harry, Matilda, and Edmund, by leading an armed rescue mission across the Iron Curtain from Romania into Tisza -Újlak (Vylock) in Soviet Subcarpathia (now Zakarpattia, Ukraine) and back. (After Irene's sister-in-law Matilda passed away at age 38 in Montreal, Edmund married Polly Baron from Radom, Masovian Voivodeship, Poland. Polly had witnessed the murder of her parents Israel and Blima Baran and brother Shaiyeh Yossle Baran, three among the 3.2 million Jewish Poles murdered in the Holocaust. Polly went to Auschwitz at age 13. She, brother Albert, and sisters Manya, Shayva Rosner, and Chava Ita survived the Holocaust.) After paying a fortune in bribes and for his service to the Kingdom of Romania, Eugene in late 1947 secured valid passports and exit visas in Bucharest, Romania's capital, to escape from Communist Europe. (In August 1948, eight months after Irene and Eugene left Romania, the Siguranța became the Departamentul Securității Statului, the vicious and Soviet NKVD-controlled Securitate protecting Communist Party Secretary Nicolae Ceaușescu with hundreds of thousands of informants.) From Romania, Irene and Eugene went to Belgium, where Eugene forged residence and work permits to be in Antwerp. Irene graduated from an ORT fashion school, summa cum laude. Canada accepted them in 1950 because of the WWII service to the British Crown of Irene's elder brother, Alex Mermelstein. Alex had fought for the Free Czech forces, stationed in Warwickshire, England, where in 1940 he married his wife Sofie Barr, a Jewish orphan from Germany. In May 1942, a team of Alex's Czech co-soldiers from Warwickshire assassinated, in a Prague suburb, SS General Reinhard Heydrich, head of the German Security Service. Heydrich was the architect of the January 1942 Wannsee Conference plans for the final solution to the Jewish question - the extermination of Europe's nine million Jews. Adolf Eichmann, later hanged in Israel as a war criminal, prepared the Conference minutes. Among Heydrich's other jobs, he commanded the Einsatzgruppen, which, trailing the German armed forces, murdered 1.3 million Jews by mass shooting and gassing. The Heydrich assassination, documented in the movie thriller Anthropoid (2016), was the only time the Allies killed a top Nazi. From Canada, Irene and Eugene moved in 1979 to Hallandale Beach, Florida, where Irene lives happily and is planning no more great escapes. Of the seven Mermelstein siblings, only Irene, the youngest, still lives. Most of Irene and Eugene's uncles, aunts, and cousins were murdered in the Holocaust. [Their lives and deaths will be told in the forthcoming book, Holocaust Houdinis.] But some survived. Here are a few of their stories: Eugene's first cousin Naftali (Tuli) Deutsch, deported at 12½ years old, survived Auschwitz and four other camps. After the war he served in the Israel Defense Forces before moving to California. In 2008 he published A Holocaust Survivor in the Footsteps of His Past. His parents and two of his brothers were murdered. His four sisters and a brother survived. One sister, Eugene's first cousin Irene Deutsch, endured Auschwitz and Bergen- Belsen. Married to the late Sam Kreitenberg, another Subcarpathian Holocaust survivor, she died in 2016 in Beverly Hills. In April 2018, during the West Point Club's 2018 Holocaust Days of Remembrance, 1st Lt. Zoe Kreitenberg, a 2016 West Point alumna and Irene and Sam's granddaughter, spoke with honor, love, and pride about her grandparents' Holocaust experiences. With her was Lt.-Gen. Robert L. Caslen, West Point's superintendent. Tuli's surviving brother was Eugene's deaf-mute first cousin Harry Dunai. Harry had numerous near-death encounters in Budapest until the Soviets liberated him at age 11. With his daughter, he published, in 2002, Surviving in Silence: A Deaf Boy in the Holocaust: The Harry I. Dunai Story. Isser Mermelstein, Eugene's first cousin, hid in the forests of Subcarpathia. Isser's brother was shot by Jew hunters who were tracking them down; three other brothers, one sister, and his parents were also murdered. But Isser and a sister survived. With Eugene and two other partners, Isser made a fortune after the war smuggling people and goods between Romania and Hungary. Eugene's first-cousin-once-removed Jack Steinmetz was deported from Subcarpathia directly into Birkenau in May-June 1944. His parents (Eugene's first cousins) and siblings were murdered in the camps. Jack was 15. He was in a bunk for youths when, during a roll call, Dr. Mengele stuck out his riding crop. The boys' heads had to reach it while walking below it. Jack wasn't tall enough to reach the riding crop. So Mengele sent him to the gas chamber. He was in the chamber's ante-room, watching SS officers stuff Jews into the gas chamber, when a German officer saved him: The officer came into the ante-room and took Jack and 13 other Jewish boys away for work details, in a story told years later in the Canadian Jewish News. (Eugene saved Jack by smuggling him to and from Romania and Hungary after the war and paid for him to be smuggled into Germany.) A cousin common to Irene and Eugene is Aranka (Meyer) Siegel, later married to Gilbert Siegal, a Harvard Law School graduate, New York City lawyer, and World War II United States Airforce officer. Aranka was deported at age 13 from Subcarpathia to Auschwitz, to Christianstadt and, following a five-week winter death march, to Bergen-Belsen. All of Aranka's siblings but one were murdered at Auschwitz. Aranka wrote a children's book about Feige Rosner, her grandmother from Komyat: Memories of Babi (2008). She also wrote two other books about the Holocaust: Upon the Head of the Goat: A Childhood in Hungary 1939-1944 (1981), and Grace in the Wilderness: After the Liberation 1945-1948 (1985). Despite the evil they witnessed, Irene and Eugene always looked for the good in people. They were defiant toward their German and Hungarian fascist tormentors. Otherwise, they were optimistic and resilient. In their hearts was love, never hate. They were filled with character and courage. And heroism. More than luck and smarts, that's how they survived the Holocaust and the years that followed. Here to light a candle are Irene Lebovits; her son and daughter-in-law Justices Gerald Lebovits and Margaret Chan; and her grandchildren Natalie and Kenneth Lebovits and Or Zaidenberg.

Sabbath candlesticks owed by Eugene Lebovits's family, the family's only possession that survived the war

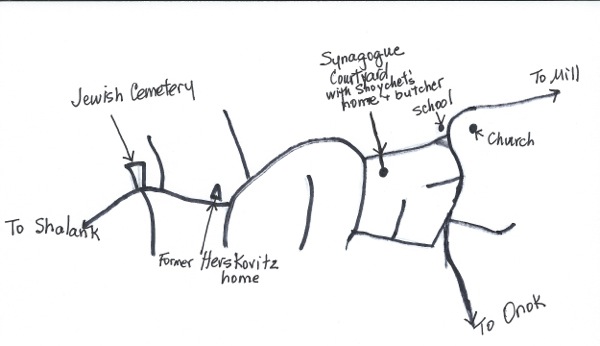

(Families mentioned- Herskovitz, Leibowitz, Gelb) Notes from various e-mails between Roberta Solit & Eti Elboim, daughter of Sara Leibowitz, 2012-2013

The Herskovitz family lived at Masricova 470. The name of the street was changed to Miklos Horthy and today is Vatutina Street. Their home was just down the street from the cemetery. Near their house they had fields of corn and wheat. My mother's house no longer exists today. On the court is established a large grocery store that was built two years ago. It is marked on the map, on the street of the Jewish cemetery.

A grocery store is now at the former location of Herskovitz home

This map, mostly of Big Komjat, shows the location of synagogue and shoycet's home, the location of former Herskovitz home, and the Jewish Cemetery. City Hall, School, and large Church are in upper right. Sara says she remembers everything about Komjat, where each family lived and where everything was. She remembers the Gelb’s family’s Inn, run by Esther Gelb and her brother Solomon-Avrum Gelb. They were cousins of Sara’s mother. Esther Gelb survived the holocaust and moved to the United States. She is no longer alive today. The children of their Gelb cousins are living in Israel. They have grandchildren and great-grandchildren. There were so many family members from her mother and father’s sides, Leibowitz’s, Gelb’s, and Herskovitz’s that probably one quarter of the population of Komjat were related to her. Sara married Shalom Leibowitz (God rest his soul) who was a cousin. He was from Satu Mare, but his family came from Komjat. Most likely many of the Leibowitz’s in Komjat are relatives of Sara’s. Sara is in touch with relatives in Israel and abroad. When the war was over, in 1945, Sara was just 16 ½. She returned to Komjat in hopes of finding family. She found none, and another family was living in the Herskovitz home. Sara left. In the summer of 2012 Sara returned to Komjat for the first time in all these years. Along with her on her return home, were her daughter Eti, and 5 grandchildren. These are some of the comments made by Sara’s daughter Eti after their trip to Komjat- “Komjat looks like a small village. Simple houses, cobbled streets, no sidewalks. Courtyards of the houses grow grapes. People who live there are very curious, and many left their homes to see who we are and why we came. There were those who wanted us to give them money. We were in the synagogue. It looks exactly like in the pictures on your site. Outside it has a coating of the timber and the inside is kind of storage. My mom says it was the small synagogue. Beside it was another synagogue, much larger and more luxurious, with an attic women's prayer. Instead there are today greenhouses. Near the synagogue, where today there is nothing, just a concrete frame, was the home of the butcher and rabbi. We visited the cemetery. We found the grave of my great-grandmother, Hannah Deborah Gelb who died in the year 1942. The tomb has a new position. The tombstone was prepared a few years ago by our relatives from the United States, who are also the grandchildren of Hannah Deborah. We conducted a very exciting ceremony there. We said Tehillim and we renewed the letters on the tombstone. By the way, my mom says that everything changed in the village. She was there last time in 1945! She says that the houses look quite different. No house looks like she can remember!" Eti wrote, my mother wanted to return to Komjat “To close the circle and commemorate all those who did not return.”

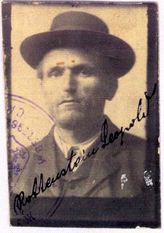

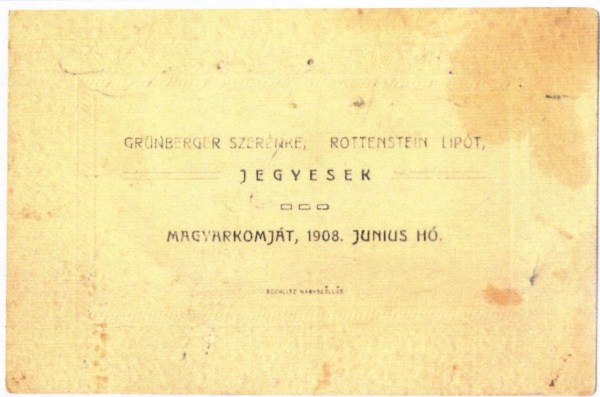

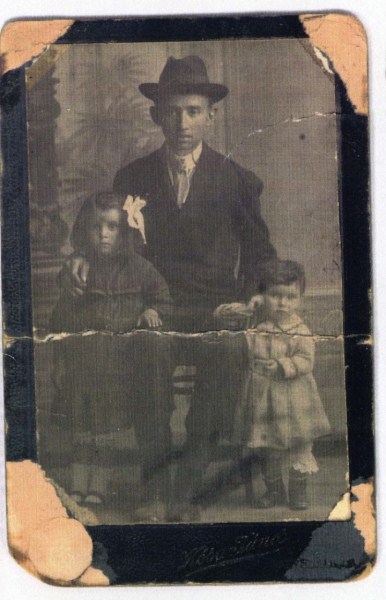

(Families mentioned– Rottenstein (Rothstein), Schwartz, Berger, Weiss, Grunberger, Gelb, Schoenfeld)Recalled by Shirley Rottenstein Krotki during visits to her home by Roberta Solit, on January 6, 1998 & February 25, 1998

(Families mentioned- Rosner, Davidovich, Siegal, Grossman) Notes taken by Roberta Solit during visits, conversations & e-mails with Aranka Siegal, December 1997, March 2012, February 2014 & May 2014

I had the great pleasure of speaking with Aranka Siegal several times and meeting her in March of 2012. She has written several books describing her time with her maternal grandmother, Feiga "Babi" Rosner who lived in Komjat.

Aranka's mother, Risa Rosner, and her parents Feiga and Noham Rosner, were all born in Komjat. When Risa was about 18, she moved to Beregszasz. She married Meyer Meizlik and on June 10th, 1930, Aranka was born. Sadly, when Aranka was only 9 months old, her father passed away. Her mother then married Ignatz Davidovich. One of her mother's sisters married a Mermelstein. Aranka and her parents remained in Beregszasz, though most holidays were celebrated at Babi's home in Komjat.

Most summers Aranka lived with Babi in Komjat. The times with Babi were precious to Aranka. The stories and lessons that Babi told Aranka are described in the wonderful book, written by Aranka called Memories of Babi. At the beginning of World War II, while visiting Babi, the borders between Hungary and Ukraine were closed. Aranka could not return to her mother in Beregszasz and she had to remain in Komjat for almost one year. She learned Ukrainian in Komjat though her Babi spoke to her in Yiddish. The last time Aranka saw Komjat was in 1941, when she was 11 years of age. That is when the border opened and she could return home to Beregszasz. One of her sisters, Rosi, later went back to her grandmother's home in Komjat. Tragically neither was ever seen again. Aranka was one of 7 children; only 3 survived the Holocaust, Aranka, a sister Etu, who lived in and raised a family in Israel, and another sister ,Violet. Violet raised a family in Connecticut and now lives in Florida, near Aranka.

Aranka spoke of two Komjats, one large and one small, one being closer to the woods (Little Komjat), and the other closer to the large Russian Orthodox church (Big Komjat.) Most of the people in Komjat were Russian Orthodox, and most were uneducated.

The land in Little Komjat was flat farmland. There were fewer Jewish people living in Little Komjat than in Big Komjat. There were two synagogues in Komjat. One was in Little Komjat, where her Babi lived. There was a courtyard with the small synagogue along with some homes. The ceiling of the synagogue was very low. People owned their own pews, made of wood, and the ark was "old fashioned". There was a mikvah in Komjat.

Aranka described the path she would take in traveling from her home in Beregszasz to Babi's home in Komjat. To get to Babi's home from Aranka's home, you would take the train in Beregszasz to the town of Komlos, today Khmil'nyk, just northwest of Komjat. You would then walk along a road that is next to the forest, west of Komjat. Following this road, you would come to Aranka's grandmother's home on the left hand side of this road, as you would walk towards the center of Komjat from Little Komjat. Her grandmother had a large parcel of land.

Many of the buildings in Komjat had roofs made of straw. The homes were white washed, the floors were dirt and the walls were thick. Shops were located inside the homes.

She remembers' her grandmother's neighbors, their names and the first names of their children. Martin Grossman, a cantor, was from Komjat and was very tall. He had a sister Yolanda, and a brother. They lived in the Synagogue courtyard. Aranka knew the Grossman's very well. She has recently, around March 2012, seen Yolanda Grossman at a survivors meeting.

The Komjat Society met in Brooklyn in the home of one of its members. Donations by it's members raised money, and among it's many good deeds, it took care of the restoration of the cemetery in Komjat. Aranka attended many of those meetings. There are some people from Komjat now living in Florida. Aranka did travel back to Beregszasz for a conference and saw that the homes appeared the same as they did 65 years ago. She regretfully did not get to visit Komjat.

Aranka has written about her life before, during and after the Holocaust in her 3 books written for young adults. They are- Upon The Head of the Goat, Grace in the Wilderness, and Memories of Babi. She has received several awards for her writing including the Newbery Honor and Boston Globe-Horn Book Award, both awarded to her in 1982. (See section – Books About Life in Komjat for more information about Aranka's books and awards).

Today Aranka is busy traveling nationally and internationally, speaking about her books, her life, and her experiences during the Holocaust. Though she has never returned, yet has thoughts about it, she still cherishes her memories of her loving grandmother and her wonderful summers spent in Komjat .

Herman (Tzvi Elimelech Smilovitz) Smilow (Families mentioned- Smilovitz, Hollander, Shomwell, Sonnenblick, Greenfield, Weiss, Merelstein and Grossman) Notes taken by Roberta Solit from several meetings and phone calls with Herman Smilow in 1997, 1998 and 2012

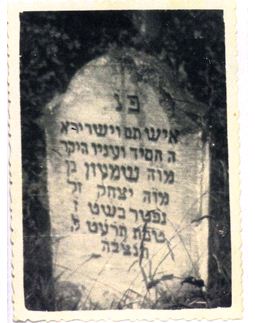

The market was across the street from the Mill and was held once per month during the summers. It probably took about an hour to walk from Magyarkomjat (Little Komjat) on the western end, to the Mill, all the way east. The market was just past the Gelb home. One of the Gelb brothers owned a restaurant and home near the Mill on the north side of the main road. Yoseph Arye Gelb, another brother, hid in Komjat when the German's were rounding them up. Someone (not Jewish) in Komjat told the gendarmerie and, the young man was caught. He was brutally murdered. All of the people that were in hiding were caught because their hiding places were uncovered by townspeople aiding the Germans. All the houses had numbers. The numbers went in order, beginning in the area where the large church and town hall was. The Smilovics lived at number 450. Next to their home was the home of Joseph Grossman's paternal grandfather. Another Grossman, son of the grandfather lived on Hadash, near the Mermelsteins. Each house had a small amount of property called 1/2 day or a day, depending on how long it took for a couple of horses to tend it. They had fruit trees and a vegetable garden. Most of the people owned the fields, but the pasture fields belonged to the town. His father leased fields from the township. In 1933 a big rain soaked out the fields, it cost them a fortune. They had beautiful cattle but had to sell them to pay the workers. They sold the young cattle and were left with one cow that would provide milk. A week before Pesach the cow died. This was the first time he ever saw his mother cry. Two times a year his family hired a horse and wagon to take them to grandmother's town to visit for the holidays of Pesach and Succoth. Everything grew in the fields of Komjat. Very few Jews actually worked in the fields. The Smilovcs home had a grocery store that was connected to the home. Szollos had wholesale houses where products for the grocery were purchased. If a family was poor and didn't have money to buy the products, Herman's father would give them credit. Then, when Herman's family needed chickens, geese or other items, his father would trade his credit for those products. Yitzak Leibowitz was the tishler, the wood craftsman of Komjat. (Tish means table). In 1940 there were no houses around the cemetery, just fields. There is a cement wall around the whole cemetery which Mr. Mermelstein, and a distant cousin of Mr. Smilow's plus some members of the Kimyater Society in NY paid for after the war, perhaps in the 1970's. He confirmed the location of the cemetery being "on a hill, on the right side of the town, running down a hill is the cemetery." The large stone in the center of the cemetery is the grave of Isadore Mermelstein's fathers'. On the left side of the cemetery is a little street. Herman needed shoes. There were two leather stores, one in Vinogradov (Szollus) and one in Irshava. He rode his bicycle to Szollus to buy some leather. In order to make a purchase, you needed to have a certain card. But Jews were not permitted to have cards. Therefore you had to buy one on the black market. While returning home to Komjat, he was stopped by the police. They asked him where he purchased the leather. He said that he bought it from someone on the street. He did not want to tell the truth, that he really bought it from a Jewish merchant in Szollus. That was illegal and the merchant would lose his shop if they found out. The police questioned him and beat him for 9 hours. They tried to get a confession out of him. But, he wouldn't tell the truth. It took him two days to wake up from the beatings he took. Returning to Komjat After the Holocaust In Oct 1994, Herman went back to Magya Komjat. He was there for two hours during which time it was pouring down rain and very grey, just as miserable as he felt. He hardly recognized his home. It had been rebuilt to the taste of the people living there. Komjat was not crowded when he lived there. Today there are many homes. He noted that people in Komjat die at an earlier age than in America. When he went looking for some of his contemporaries, he found that they were no longer living. This was true for even people that were younger than him. His nextdoor neighbors, 2 sisters, were still alive. The people he met were children of people who were not married when he was living there. For example- he met a woman, Margeta Vasilove (her father was Vasil), who was a young girl of 9 when he lived there. While they were speaking he mentioned his name and that of his family members. Margeta's mother was a wet-nurse. Margeta recalled that her mother speaking of a women, Herman's mother, who had a boy baby that she nursed when the mother had to leave for a while. To find her home, go straight from the cemetery, about the same distance from the beginning of the town to the cemetery. She lives there, across from the where the Beit Midrasch is, near Joseph Grossmans' grandfather's home. There was a beautiful mill that was driven by water. When Herman visited, the river was dry and the mill was abandoned. He visited the courtyard in Big Komjat that contained the Shul, the Beit Midrash and the foundation of the shochet's home. The doors to both were locked. He was told that no one ever goes in these doors. It was late already, too late to find keys. Both are standing, as they were. When he visitied the cemetery that day in 1994 there was only one recognizable stone, that of the father of Mr. Mermelstein. The others were lying down on the earth, toppled. It was difficult to read the stones, they were worn and chipped and the writing was in Yiddish-Hebrew. He could not find his grandparents stones. It was raining very hard. He went down the hill in the cemetery and said his prayers.

(Families mentioned- Zelmanovitz, Engerman, Weiss, Leibowich, Steinberg, Teitlebaum) From conversation between Jack Zelman and Roberta Solit, February 22,1998 Jack Zelman (nee Zelmanovitz) was born in Komjat in 1924. "My parents were first cousins, my mother was Florence Zelmanovitz and my father was an Engerman. Because they were first cousins, they were only recognized by Jewish law, not the other (Czeck). The children all have my mother's maiden name, Zelmanovitz. I've never told this to anyone, my son might not even know this. Joseph Gossman is a cousin of mine. My mother Florence and Joseph's mother Malvine, were sisters. Komyat had so much mud, and no electricity. We were very poor. I had no shoes. We did anything to make money. I used to bring dead people to the place where they prepared the bodies. I dug graves for pennies. We did anything we could. A meal was a piece of rye bread and salt. We stole food from other families. One day I brought a chicken to the shoychet. The chicken ran away, I ran to get it and was late to class. This made the teacher, Rabbi Weiss, the shoychet, very upset and he hit me. We called him rabbi, but he probably wasn't really a rabbi. My father wanted me to cut the grass. My father was very strict and so was the Rabbi. Every year a new teacher came to Komjat. So, I was 9 years old, and I ran away from Komjat "to a big city". That city was Kiralyhaza, where 4 of my Zelmanovitz uncles lived. Moishe Zelmanovitz was a furniture and carpet maker who made a poor living. The other three, Shama, Elaizer and Shumlach were all bakers.

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Home | Maps | Jewish History of Velikiye Komyaty | Description of Town | Religious Leaders & Synagogue | Holocaust | Cemetery | Databases | Photos | Testomonies & Interviews | Books about Life in Komjat | B'nai Kimyater Society & Miscellaneous |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Photo on left- Dorothy on the left, Shirley on the right with Nutan Grunberger, their mother's

brother, taken in Nagyszollos, ca. 1916. Photo taken by Kosa

Janos, Nagyszollos.

Photo on left- Dorothy on the left, Shirley on the right with Nutan Grunberger, their mother's

brother, taken in Nagyszollos, ca. 1916. Photo taken by Kosa

Janos, Nagyszollos.

Henya Rottenstein and grandson David Berger, son of Henya's daughter

Gitel Berger, taken in Komjat before the holocaust. (See article

"Stowaway Killed…." 1937 in Miscellaneous section)

Henya Rottenstein and grandson David Berger, son of Henya's daughter

Gitel Berger, taken in Komjat before the holocaust. (See article

"Stowaway Killed…." 1937 in Miscellaneous section)

Herman Smilow, NY, 1998

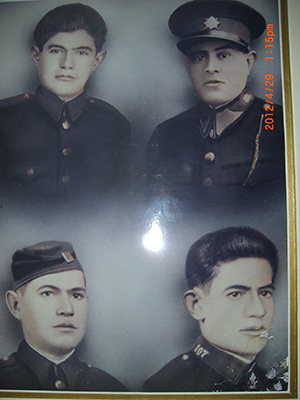

Herman Smilow, NY, 1998 4 Zelmanvitz Brothers

4 Zelmanvitz Brothers